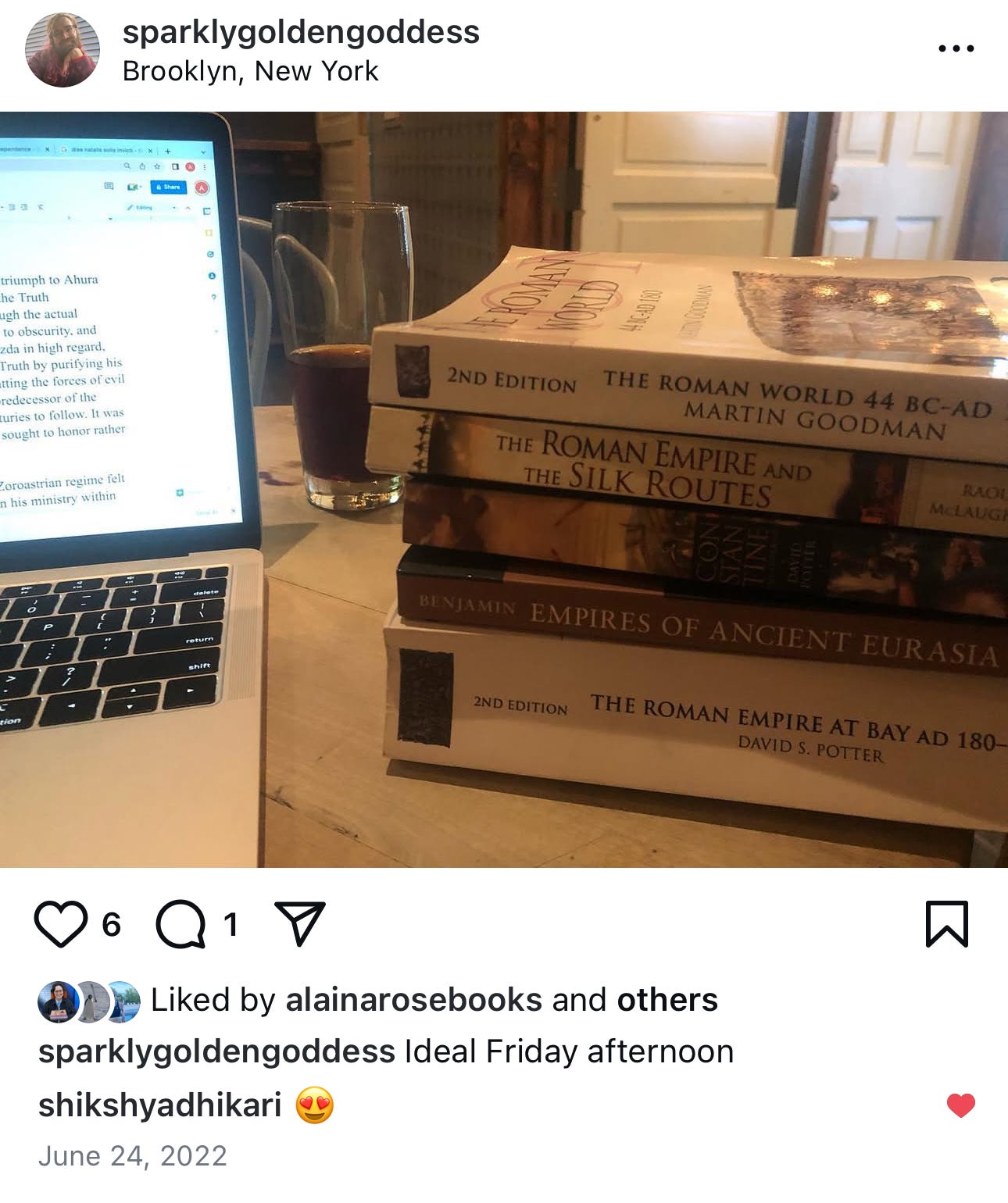

A Journey in Antiquity from Britain to Afghanistan (June 25, 2022, the severed branch)

From York to Rome | Tunisia and Egypt | Lebanon | onward from Syria by caravan | Persia, Turkmenistan, and Afghanistan | Christians, Zoroastrians, and Manichaeans | What Ifs and China-Rome Relations

world history: all my links in one place ! 💖⭐️🌟💫💗💞🧙🌍🌏🌎

Proceed chronologically or start with any topic!

Above: Constantine in the Battle of Milvian Bridge, the Angels of God above (wikimedia)

Part 2:

A Journey in Antiquity from Afghanistan to China (July 2, 2022, the severed branch)

Above: The Pamir Mountains, a central barrier between Western and Eastern Asia (wikimedia)

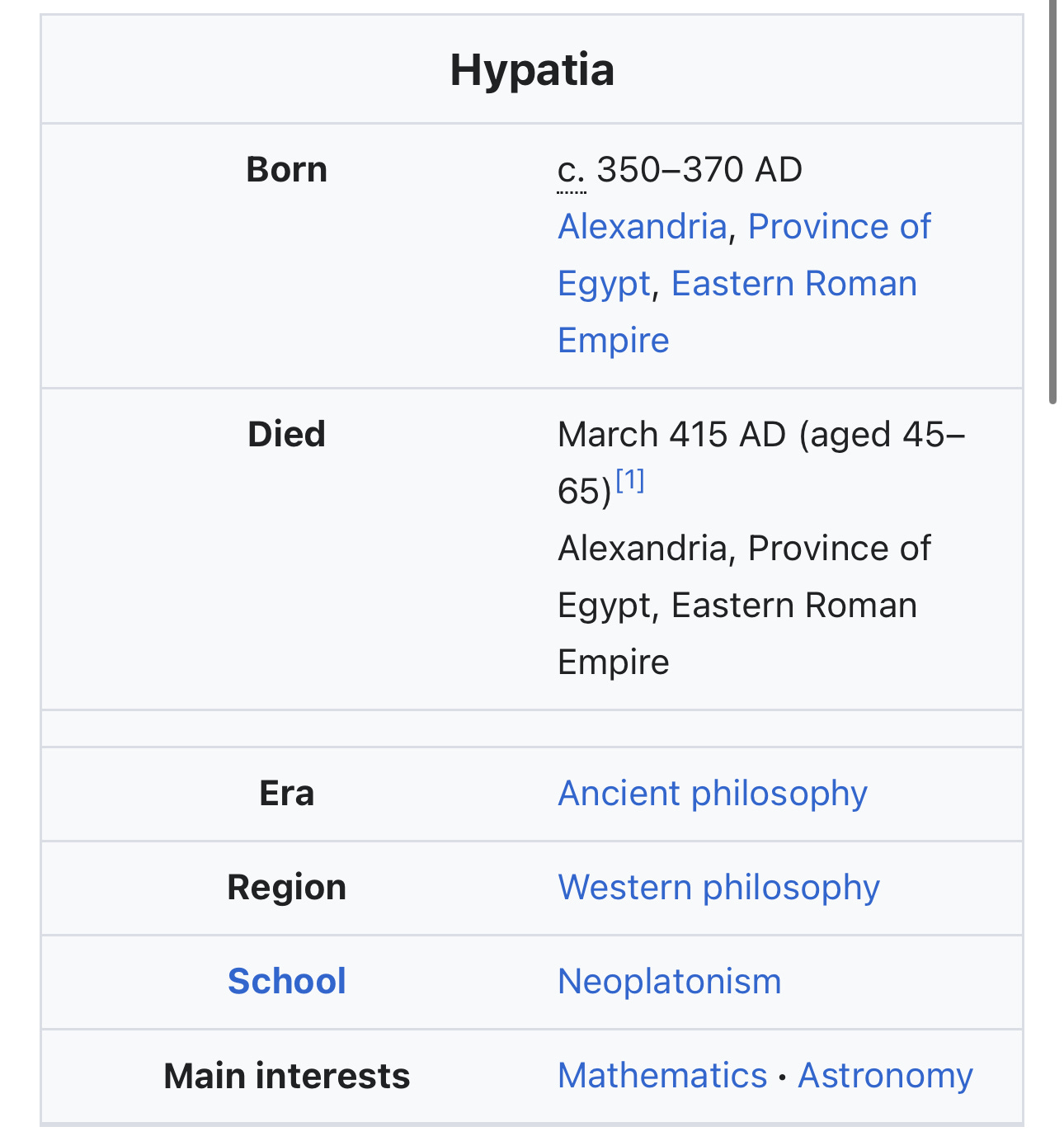

shared credit with Craig Benjamin, Martin Goodman, Raoul McLaughlin, and David Potter, crucial sources for this writing: special thank you to Goodman for his research on Alexandria and Ptolemaic Egypt ❤️

Although I have long glamorized lengthy journeys across the surface of this great celestial body, I have yet to attain my dream of traveling across Eurasia in the third and fourth centuries AD. I can hardly choose between these two centuries, and so I suppose I would simply move through both simultaneously. Easy enough in theory. I can purchase the necessary maps. So why, I sometimes wonder, have I failed so disastrously to achieve this dream? My disgrace as an explorer is certainly not for lack of research. Through the diligent study of ancient European roads, Indian Ocean shipping routes, and narrow mountain passes through the Himalayas, I have spent many long hours in my apartment frantically devising my improbable adventures.

My journey begins with a Roman legionary garrison in York, from which I travel by road and boat to the Eternal City in Italy. In the reverse, I move upon those same sacred roads which Constantine took in the early 300s as a young man. Beginning in modern Serbia, he fled the palace of that determined persecutor of Christians, the Emperor Galerius. Supposedly, Galerius planned on ordering Constantine’s execution just before the future author of the Nicene Creed fled, but he got too drunk during a long bout of orgiastic fun and fell asleep. When he awoke, his victim was gone.

A contender for the throne, Constantine had been warned by his father in Britain to fear for his life. And so, following the direct orders of his paterfamilias, he moved swiftly by road all the way from Serbia to the English Channel. He killed the post horses behind him so that his pursuers could not reach him (of course, I trust that I shall have no reason to slaughter those gentle beasts!) Then, crossing over to Britain by ship, he was reunited with his father the co-Emperor Constantius in York. There, upon his father’s death, his soldiers proclaimed him Caesar.

As I am unable to resist a visit to Rome on my way to China, I do not follow Constantine’s path all the way back to Serbia. Instead, I follow his subsequent journey from Gaul (modern France) to Italy. In Gaul, I behold Constantine displaying his earliest signs of Christian mercy: he feeds some captured Frankish kings to wild beasts in the amphitheater. And then from here, he launches his great invasion of Italy against the usurper emperor Maxentius. Remembering the gruesome deaths of his Germanic victims, I join him for this great event, and together we cross the Alps from France. With his army, I emerge from the mountains into northern Italy.

On the outskirts of Rome, I stand beside him. We gaze up into the stars. A great cross appears aflame in the sky. Alongside it is a message from Christ that says “by this sign conquer.” We paint the symbol of Christ the Lord on the shields of all the soldiers, and then together we advance toward the city of Rome. Thus I participate (only as an onlooker, I hope, for I am far too cowardly for warfare!) in the Battle of Milvian Bridge in AD 312. Constantine’s victory there, in one of the most foundational conflicts of human history, then sets the stage for the transformation of the Roman Empire from pagan to Christian. And I am at his side, frightfully concealed behind his lines.

From Rome, I make my way down the river Tiber to the harbor city of Ostia on the Italian coast. There I board a ship bound for Carthage in modern Tunisia. Carthage was once Rome’s mortal enemy, but today, like Egypt, it serves as the port through which passes a great bulk of Rome’s grain. Without the grain flowing constantly from the lush and fertile soil of North Africa to the hungry poor of Rome, most of Rome’s million inhabitants would starve to death in the streets. The Roman government thus subsidizes an extensive network of ships which transports not only grain from Africa to Rome, but also many other goods between ports around the Mediterranean.

Alas, I can see the future as I disembark into this immense Phoenician city. Some 130 years from now in 439, the barbarian Vandals will audaciously cross to Africa from Spain. Taking the Romans by surprise, they will capture the poorly defended Carthage. The whole fate of the Western Empire, cut off from control over its vital African supplies, will hang in the balance. Striving to secure the most important source of wealth for their European lands, the Eastern Romans will bankrupt themselves building a navy to reconquer Carthage. But thanks to foolhardy tactics, the Vandals will destroy nearly all their ships. The Western Roman Empire, unable to fund its armies or reliably feed its people, will fall to the northern barbarians.

Walking through the streets of Carthage knowing both the past which was and the future which will come, I wonder at the wealth of this great African city on which Rome so critically depends. How strange, I think, that the Romans were once so fearful of Carthage that they destroyed it and sold its whole population into slavery, all to prevent its potential re-emergence as a Mediterranean power. And yet how badly they need it now. How vital is a rebuilt Carthage to their power in the early 300s!

Above: In red, the Roman province of Africa Proconsularis, home to Carthage (wikipedia)

But in the volatile times at the dawn of the fourth century, there are other issues at play. Control of Carthage seems secure. The Great Persecution of the Christians, initiated under the Emperors Diocletian and Galerius, is still fresh in the minds of everyone. Under the reign of the Christian Constantine, the North African Christians bicker over how to treat those priests who were fearful enough to hand over scriptures for burning by the authorities. There are riots and bloodshed as bishops who cooperated are denounced as illegitimate; some argue that every baptism those traitors gave is forfeit. And as Constantine attempts to return the control of church property to the Christians, they demonstrate in the streets to prevent any keys from being handed over to those bishops suspected of accommodating the persecutors.

Exciting as it is to be a time traveling tourist in a quasi war zone, I step away briefly from the blood-soaked streets. I seek instead to mingle with the shadows of the man who was perhaps the first Christian theologian - the Berber Tertullian of Carthage (AD 160 - 220). His words, fantasizing about the glorious flames of Hell, no doubt gave courage to the Christians being persecuted during the reign of Diocletian:

“You who are fond of spectacles, expect the greatest of all spectacles, the last and eternal judgment of the universe. How shall I admire, how laugh, how rejoice, how exult, when I behold so many proud monarchs, and fancied gods, groaning in the lowest abyss of darkness; so many magistrates who persecuted the name of the Lord, liquefying in fiercer fires than they ever kindled against the Christians; so many sage philosophers blushing in red hot flames with their deluded scholars; so many celebrated poets trembling before the tribunal, not of Minos, but of Christ; so many tragedians, more tuneful in the expression of their own sufferings; so many dancers tripping more nimbly from anguish than ever before from applause.”

Such passionate words! The rich cultural life of Carthage clearly enraged this sanctimonious religious elder. How sad and perhaps tantalizing for Tertullian that, for the tragic error of having later adopted doctrines which the Catholic Church was to condemn, he today burns in Hell alongside all those actresses he wanted and despised. There he is in the company of another Church Father, Origen of Alexandria (AD 185 - 253). According to one story immortalized by the church historian Eusebius of Caesarea, Origen was so devoted to resisting the temptations of the flesh that he castrated himself. Alas, despite having removed the source of those sexual inclinations which might have lured into his imagination the lush bodies performing so enticingly upon the stages of North Africa’s depraved theaters, his mind sadly succumbed to false beliefs regarding the Trinity. For this, a few short centuries after pagan authorities brutally tortured him for his most self-destructive faith in Christ, the second council of Constantinople usurped the declared authority of the Lord Jesus Christ and, by their own initiative, declared that great saint’s soul condemned (AD 552). He now finds himself in Hell beside Tertullian and the luscious dancers.

Having enjoyed my contemplations of early Christian strife beneath the hot Tunisian sun, I board a merchant ship bound to move along the coast to Alexandria. Egypt, like Carthage, is vital for the Roman Empire, producing much of the grain which feeds the numerous plebeians in Rome. So too will it be vital in the future for Constantinople, whose population it shall sustain once Constantine founds that new capital. Egypt is considered so economically pivotal to the Romans that no Roman of senatorial rank is permitted to set foot here without express permission from the emperor. This is for fear that he may seize control of Egyptian grain and use it as leverage in a bid to seize the purple for himself. Fortunately, as a lowly time traveler with Roman citizenship but no claim to the throne, I pass through the port controls without an issue.

By the early 300s AD, foreigners have been exploiting the native Egyptian population for nearly a millennium. First, they were conquered by the Persians. These needed to put down repeated rebellions, but they never established a truly effective administrative structure for fully extracting the riches of the population. But then, in 323 BC, nearly two centuries of fruitful subjugation under the Greco-Macedonian Ptolemaic dynasty began. In the two centuries before Cleopatra, the last Greek ruler of Egypt, was finally defeated by the Romans at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, the Ptolemies reigned over a highly efficient system of exploitation. They enriched themselves off the Nile’s immense agricultural wealth while simultaneously building Alexandria into a superbly profitable center of trade and learning.

The function of Greco-Macedonian government was to ruthlessly ensure the constant flow of riches from the mercilessly taxed peasantry up to the elites and then into the coffers of the royal family. Military garrisons in the countryside guaranteed that peasant-generated surpluses would move down the Nile into Alexandria. There, these could be exported across the Mediterranean, attracting an inflow of gold and silver from Europe to further benefit the Greek royals. To support all this, the Ptolemies built a highly sophisticated administrative structure which kept close records of every human, animal, and village, always striving to assure that no living thing could escape some profitable use. For the native Egyptians, the surest path to any kind of power in the bureaucracy was to dilute their indigenous ways with Hellenistic customs.

With the resources accumulating in their treasury, the idle kings and queens lazily commissioned the construction of their own elaborate special quarter of the city. It was complete with a massive royal palace, a legendary library, and even a museum. When the Romans conquered Egypt, they inherited this system and appropriated it for their own benefit. Granted, Julius Caesar accidentally burned down part of the library, but this could hardly undermine later Roman ambitions to harness Egypt’s wealth for Rome’s own ends. Adding their own reforms but also leaving many of the Ptolemaic administrative structures intact, the Romans directed ever-larger chunks of Egypt’s riches toward Italy, while leaving many of the Greco-Macedonian elites in positions of local power to accomplish their dirty work. Garrisons of Roman legions in Alexandria still help ensure the flow of grain to Rome’s growing population.

Despite these brutal realities, there remains something enticing about Alexandria’s learning, industry, and commerce. The great capital’s workshops buzz throughout the day with the manufacture of glassware and mosaics for export across the Mediterranean. Meanwhile, spices from India and silk from China arrive at Red Sea ports, move by road to the Nile, and then flow downriver for further processing around Alexandria’s great harbor. Christian theologians and pagan philosophers study both sacred and secular texts late into the night by candlelight, while some of the most important advances in medicine occur within the city’s renowned schools. Some of the smartest and most educated people from Europe, Asia, and Africa gather here to study and converse. But what I seek is a more underground movement.

Despite all the surface-level religious syncretism blending Greco-Roman and Egyptian traditions, there remain secretive societies of native Egyptians who yearn to overthrow their foreign overlords. Their dissident texts, with origins stretching back to the early days of Ptolemaic rule almost six hundred years ago, still circulate at the dawn of the fourth century AD. In one of them, The Oracle of the Potter, an unknown writer prophesies the day of Egyptian liberation. Alexandria, they hope, will be destroyed, and the ancient Egyptian capital of Memphis will rise again from the shadows of the pyramids. Yet for now, Roman officials and Greco-Macedonian elites continue to dominate Egypt’s politics. The most recent rebellion was in 297 AD, when several imperial officials revolted and declared themselves emperor, requiring intervention into Egypt by Roman forces to maintain control. When there are revolts, in other words, they are the handiwork of foreign elites, not natives. The prophesied revival of Egypt as its own independent country will need to wait another 1600 years.

From Alexandria, I might journey upriver to the Greco-Roman ports which dot the Red Sea coastline. From there I could board a ship of Tamil merchants bound for India. We would stop along the way at the many trade cities scattered along the coast of Arabia before allowing the monsoon winds to carry us off to the subcontinent. For all the mysteries of geography in late antiquity, where nearly no Roman or Chinese travelers ever succeed in reaching the other empire, it might be the Tamils who do indeed move between each of these civilizations. They trade, after all, across a vast oceanic network stretching from Egypt to Arabia to Sri Lanka to Southeast Asia; their settlements and businesses can be found in many Greco-Roman Red Sea cities. Sadly, like most business-focused merchants, they have left limited literary records.

Alas, I do long to follow in the footsteps of the Roman diplomats who, following these same Tamil trade routes in the late second century, made it via Southeast Asia all the way to Han China. Tragically, although Chinese records confirm their successful arrival and conveyance of gifts to the emperor, they apparently did not survive the return journey to Rome. Rather than following these treacherous sea routes, however, I am far too tempted by the opportunity to make my way overland through Persia.

I board a merchant ship in Alexandria bound for Tyre in modern Lebanon. There I disembark in another ancient Phoenician city under the control of the Romans, and it is from Tyre that I shall follow in the footsteps of one of the era’s greatest travelers: Maes, a Syrian merchant whose base of operations was here. Incredibly, in a world where most trade between China and Rome was conducted only through middlemen, Maes and his audacious agents traveled all the way from Roman Syria to the edges of China, reaching what for the Romans was then the edge of the known world: the semi-mythical “Stone Tower” in the center of Eurasia, the exact location of which is still unknown to historians. From there, in a quest to cut out the middlemen and directly purchase raw Chinese silk for import to Syria, the eager Maes dispatched several of his agents onward into China. Unfortunately, it is again aristocrats rather than merchants who wrote much of ancient history. But one of those aristocrats - the Greek geographer Ptolemy, author of Geography in 150 AD - used the records of Maes as a source for describing the world as he knew it. It is through the diligent study of these brave merchants’ adventures that I can chart my overland course toward China.

From Phoenician Tyre, I journey northward, passing through Tyre’s longtime rival in competitions for imperial favor - the Roman-founded colony of Beruit - before at last reaching the Syrian city of Antioch. By now in the early 300s AD, Antioch is a crucial base for Roman military operations against the Persians. But only a few decades ago, Antioch was controlled by the Arab Queen Zenobia of Palmyra, a legendary Silk Road city whose brief independence was crushed by the Roman Emperor Aurelian in the early 270s during his reunification of the Roman Empire. Yet for all these political dramas, and for all Palmyra’s history as a wealthy and bustling caravan city playing host to the constant arrivals and departures of Greco-Roman, Arab, and Persian merchants, the most influential Syrian contribution was religious: the sun god Sol Invictus, Invincible Sun, to whom Aurelian credited his restoration of Roman control.

Above: Sol Invictus, the Invincible Sun (wikimedia)

Sol Invictus, whose main temple had long been located in the Arab city of Emesa, was also Constantine’s god. This was the god whom Constantine believed to act in his aid against his enemies; this was the god whom he placed on his earliest coins. As Sol Invictus became more prominent in the Roman Empire after Aurelian’s victory in Syria, there emerges the question of whether there is a meaningful difference between Sol Invictus and Christ. As David Potter puts it in his book Constantine the Emperor:

“In 312, Constantine’s god was both the Sun and the Christian God. It may not have been hard to make this leap, for in some Christian communities the sun god was already equated with Christ…. [Some Christians] saw the sun as their god, facing the rising sun as they prayed. Lactantius himself [a Christian writer] would observe that ‘the east is attached to God because he is the source of light and the illuminator of the world and he makes us rise toward eternal life.’”

While in Syria, I cannot help but stop to pay my respects at the temple of Sol Invictus in Emesa. If there is any God whom I truly worship personally, it is indeed Sol Invictus, whom I see every day in the sky. I know Him, from simple experience and basic instinct, to be the source of all life and light. It is no wonder that Christmas, with a date falling near the winter solstice on December 25, coincides perfectly with the date established by Aurelian for the festivals commemorating Dies Natalis Solis Invicti (the Birth of the Invincible Sun). To me, Christmas is a celebration of the light bestowed upon us by the Sun as it commences its rebirth during the darkest part of winter. And although many of the details for this whole religious transformation remain obscure and confusing, perhaps we have the ancient Syrian sun god to thank for the holiday.

In Antioch, I join up with a merchant caravan heading into Sasanian Persia. At last, I can commence my treacherous journey across that storied empire. The religiously fundamentalist Sasanian dynasty, founded in the 220s AD, seeks to restore the old glory of ancient Achaemenid Persia. It is in the name of imperial and Zoroastrian restoration that these new Persian rulers seek to conquer the Eastern Roman Empire, and it was in the midst of their attempts that they captured the Roman Emperor Valerian in AD 260. Supposedly, the Persian king then used him as a footstool, although some sources claim he was also put in charge of various engineering projects.

Like the Sasasnian kings, I too yearn to bow down in worship of the great Zoroastrian god Ahura Mazda. He was the supreme being guiding all those conquering Achaemenid kings of the sixth and fifth centuries BC: Cyrus, Darius, Xerxes. I have always found myself far more taken in by the enlightened and tolerant autocracy of Cyrus, ruler of the world’s first great empire stretching from Egypt to India, than by the now extinguished democracy of puny little Athens.

Yes, in terms of the ancient world, it is not the democratic principles of the Athenians but rather the benevolent authoritarianism of the Achaemenids, linking so many languages and gods, which really inspires not only my imagination but also my ardent adoration. I too might have followed the great god Ahura Mazda while honoring the lesser deities of those grateful peoples whom Cyrus conquered, such as the Jews whom he liberated from Babylon. Enlightened despotism indeed. There is a reason, after all, why the Judeo-Christian scriptures celebrate the Persians but not the Greeks.

And yet as I arrive today in the revivalist Sasanian Empire of the early fourth century, it is to my grave disappointment that I discover a version of Zoroastrianism which is eager not to integrate but to eliminate all other religions. Here is a regime stupendously decayed from the lost glory which it hopes to emulate. When compared with the most dogmatic elements of Christianity, the intolerant and puritanical Zoroastrianism of the Sasanians certainly falls within the flavor of the times.

Ardashir, founder of the Sasanian dynasty in 224 AD, credited his triumph over the neighboring kings and tribes of Iran to the Zoroastrian god Ahura Mazda. Ardashir and the priests who surrounded him conceived of a cosmological battle between the Truth (represented by Ahura Mazda) and the Lie (represented by Ahriman). Although the actual teachings of the religion’s semi-mythical founder, Zoroaster, are mostly lost to obscurity, and all we know for sure is that the Achaemenids included Ahura Mazda as supreme in their pantheon, King Ardashir was a zealous believer in his duty to represent the Truth by purifying his society of the Lie.

The Sasanian dynasty ultimately yielded control over all religious policy to radical Zoroastrian priests like the notorious bigot Kartir. With the fanatical Zoroastrian magi serving as an ultimate judiciary by the end of the third century, the persecution of minority religions such as Christians, Buddhists, Jews, and Manichaeans became an ideal routine. As minority religious communities continued across the empire, the success of these efforts is unclear. Yet the spirit behind these purification initiatives was a far cry from the more ancient Achaemenid dynasty, which had pragmatically honored rather than destroyed the gods of those people whom they conquered.

With such a black and white mindset, it is no wonder that the Sasanians’ Zoroastrian regime came to feel threatened by the teachings of the prophet Mani (AD 216 - 274). Manichaeism, founded in Persia and combining Zoroastrian, Christian, and pagan influences, understood reality as a perpetual struggle between Light and Darkness. Mani himself, born in the early third century in Persia, was initially well received in the court of the Sasanian king Sapor I, who showed an interest in his teachings. Mani traveled widely, especially in India, and wrote numerous works of scripture which were disseminated all across the trade and missionary routes of Eurasia. His religion would eventually spread from Europe to China. Even the great North African Christian theologian Augustine would also follow it for a while.

The Roman Emperor Diocletian, a paranoid xenophobe who was anxious to preserve the oldest Roman traditions, was as disturbed by Manichaeism as he was by Christianity. Perhaps even more so, since he saw Zoroastrianism as a nefarious Persian influence. He described the Manichaeans as having “advanced, like strange and unexpected portents, from the Persian people, our enemy, to this part of the world,” and he feared that “they may try, with the accursed customs and perverse laws of the Persians, to infect men of a more innocent nature, namely the temperate and tranquil Roman people, as well as our entire empire, with what one may call their malevolent poisons.” And yet despite Roman fears of Manichaeism as a Persian fifth column, it was the frighteningly enthusiastic Zoroastrian priest Kartir who, criticizing the Sasanian kings for being insufficiently devout, crucified Mani. Thus the Manichaeans - whose Persian influence Diocletian so dreaded - were even more persecuted in Persia, where their founder was executed for undermining traditional Persian religion. This is all characteristic of the era. Across the region, age-old religious pluralism was giving way to a strident and confused intolerance as new spiritualities spread and the defenders of the old gods felt suddenly threatened. The new religions, meanwhile, presented stark ideas of good versus evil.

Above: Ardashir receives the ring of kingship from the supreme god Ahura Mazda (wikipedia)

It was all the worse when these simmering religious tensions were caught up in the seemingly eternal rivalry between Rome and Persia. The Persians certainly reciprocated Diocletian’s feelings, and the two empires repeatedly went to war with one another, the lands between them changing hands over the centuries. And just as the Romans suspected that the Manichaeans might be Persian implants, so too did Sasanian officials perceive that Christians in Persia felt loyalty for Rome. This was a problem which was only be exacerbated once the Christian Emperor Constantine took full power over the Roman Empire. By crossing Persia in this context, I conduct a journey which few Roman travelers would ever have achieved.

The Persians frequently lived in fear that the Romans and Chinese might make direct contact and scheme mischiefs against them. For the Romans, China was a distant land they called “Seres” from whence came their silk; for the Chinese, the Romans were known as “Great China,” named as such because the Chinese understood there was a an empire similar to their own in some unknown western location. Beyond this, they were each mostly ignorant, and it was in the Persian interest for it to stay that way. They strove to prevent any Roman or Chinese travelers from crossing their territory.

There were attempts. A Chinese general, seeking contact with the Romans in 97 AD, dispatched an embassy to find the Romans by crossing Persia. I think of these explorers when my caravan reaches the trade city of Characene near the Persian Gulf. It was here, so close to their goal, where the Chinese adventurers abandoned their attempt. The Persians told the Chinese diplomats that Rome lay a three months’ journey across the ocean. The embassy thus gave up its efforts and turned back.

I, however, shall continue onward with my caravan, tracing the routes to the Stone Tower outlined by that brave Syrian merchant known as Maes. Our lengthy journey traversing the extensive roads which criss-cross the Sasanian Empire takes us through the city of Merv in modern Turkmenistan. There, I encounter Christians of a different variety than those left behind in North Africa. These Christian communities will over the coming centuries be increasingly cut off from the decisions being made for them in Rome and Constantinople. Here they live side-by-side with Buddhists and Manichaeans, worshipping precariously under the watchful gaze of Ahura Mazda. The streets of Merv are abuzz not only with the worshippers of various religions, but also with the varied tongues of merchants from South Asia, Persia, and Sogdia. Zoroastrian dreams of religious and cultural uniformity seem hopeless here. Caravans arrive from all directions - exchanging goods, discussing ideas, wandering through the markets, sleeping in the caravansaries, then turning back from whence they came. People from dizzying varieties of culture all interact here, learning from each other.

I join a group of Sogdian merchants heading east. Eventually we reach Bactria in modern Afghanistan. Once controlled by Indo-Greek kings and later by the Kushans, Bactria in the early 300s is, like Merv, under Sasanian rule. But all across the mountainous terrain, I still see the towering stupas and gigantic Buddha statues, funded long ago by the devout Buddhist Kushan kings before their empire mysteriously collapsed in the late second century. Stepping into the city of Bactra’s legendary market, I peruse goods from China, India, Europe, and Africa, and I am astonished to have finally arrived at approximately the halfway point in my journey. I am far away now from the trying feuds of the North African Christians. I cannot help but think of one of history’s greatest travelers, the Han Chinese explorer Zhang Qian.

The brave envoy Zhang Qian spent twelve years outside his homeland, some four centuries before my own arrival here. He was in the service of the Han Emperor Wudi, seeking to make contact with a potential ally in the struggle against the pastoral Xiongnu tribes against whom China was almost constantly at war. When he returned, having been long presumed dead, he changed China’s entire conception of the world.

His journey began with difficulties in 137 BC. The Xiongnu quickly captured Zhang Qian and his whole party; they killed nearly everyone but him. He was allowed to live in captivity. But though he started a family in Xiongnu lands, he never forgot his orders. After ten years, escaped his captors and fearlessly pressing deeper into Asia, apparently bringing his wife and children with him. Reaching the city of Bactra, he was startled in this very market to discover Chinese silk for sale - and in a kingdom which China had no idea even existed! As so often, then, it had been merchants who, though leaving no literary records over the course of their single-minded zeal for commerce, had nurtured the first connections between distant civilizations. Once Zhang Qian returned to Wudi’s court and shared these findings, China would be forever aware of the vast world of civilization which existed beyond its frontiers.

Above: In orange, Zhang Qian’s journey to the West (Balkh = Bactra) (wikipedia)

Eagerly purchasing some Chinese silk in this eclectic marketplace, where it is far cheaper than that available further west, I pause and remember that incredible traveler’s achievements. Having reached the city which was his final destination, I am inspired to reverse his path all the way to the Pacific. But China, from here, is still so incredibly far away. Reaching it will require strenuous passage through awesome mountains and deadly deserts. Alas, already dizzied by the religions and cultures and ecosystems through which I have passed, I am struck by the need to take my rest.

Lingering in Bactria, I contemplate what might have been different had the Romans and the Chinese succeeded through their explorers in establishing regular and direct relations. How might it have changed the Roman worldview to have actually encountered China rather than simply purchasing its silk through middlemen? Roman imperial ideology imagined its empire as a solitary fortress of universal civilization surrounded by literal and figurative walls which (precariously) kept at bay the ignorant and uncultivated forces of the barbarian world. The Roman Emperor was not just ruler of Rome; he was ruler of the world. Beyond Hadrian’s Wall in Britain, the Rhein in Western Europe, and the Danube running across the Balkans there lingered the ignorant peoples who, unlike Rome’s integrated subjects, had simply yet to benefit from its bathhouses, amphitheaters, cooking, forums, temples, and literature. In the Roman mind, only Persia had any remote claim to a rival civilization, and perhaps this is partly why the Romans hated them so much. These, Rome imagined, were the only truly significant two powers in the world, and the Persians hardly counted.

Meanwhile, the Chinese, about whom the Romans knew little, were far more advanced in a variety of arenas. Where Rome had arrows, China possessed the crossbows which would not find widespread use in Europe for another thousand years. China’s superior metallurgy also granted it substantially stronger armor, weaponry, and agricultural tools. And where Rome struggled to organize itself both administratively and educationally, China possessed paper, specialized bureaucracy, and state-organized schools for its officials.

Had Roman envoys succeeded in traveling all the way to China and back, had regular communication been established across the routes which only merchants traversed (and supposedly never in their entirety), how might this have changed the Roman worldview? Perhaps not much, admittedly, as imperial ideology could hardly be willing to concede any points. And yet how might it have accelerated the advancement of human civilization in general if these two ancient empires, while further integrating India, had somehow been able to combine their technological and cultural achievements through ever-closer diplomatic and commercial ties, even if against the backdrop of perpetual rivalry and tension?

Alas, the distances were too great for these questions to find answers. The journeys across mountains, deserts, forests, and ocean were far too perilous, expensive, and time-consuming for almost any individual person to complete, let alone for the establishment of regular diplomatic intercourse. And yet some brave pioneers - the Romans who traveled via the ocean and the Chinese explorer who was deceived from his course in Persia - did in fact set forth on adventures that, like the daring journey of Zhang Qian, just might have changed the course of history had they succeeded.

The first half of my travels are at last complete. Once I have rested, I shall commence my perilous journey east toward the great Chinese trade city of Chang’an.

Sources:

Craig Benjamin, Empires of Ancient Eurasia

Martin Goodman, The Roman World 44 BC - AD 180 (2nd edition)

Raoul McLaughlin, The Roman Empire and the Silk Routes

David Potter, Constantine the Emperor

David Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay AD 180 - 395 (2nd edition)

A Journey in Antiquity from Afghanistan to China (July 2, 2022, the severed branch)

Above: The Pamir Mountains, a central barrier between Western and Eastern Asia (wikimedia)