Daphne & Sebastian: Part Three (Daphne's Network; the Bishop of Rome)

a novella of war, politics, theater, sports, and religion

enjoying Daphne & Sebastian? make my day with a like, restack, or share!

Daphne & Sebastian (all links)

💖 snowflakeangelbutterfly 💖 is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Daphne and the Archbishop of Ravenna

Daphne was somewhat surprised to find herself missing Sebastian while he was on campaign. She had seduced him with her sexuality and intellect in order to accomplish a purpose. Now she faced a mystery: what exactly was that purpose?

She could rattle off all her formal reasons for having married Sebastian: he was a powerful man and she could be powerful by his side; she could become an empress; she could see Constantinople and other places around the Empire; she could escape from Ravenna before the city fell to some deadly force.

She still believed that most of the Empire’s lands were doomed and Constantinople was the only place she could ever be forever safe from invading armies. With Sebastian being her ticket to the capital one day, it made sense that she would worry about Sebastian’s safety, but to miss him?

She remembered how he spoke to her during their first meeting. He called her a harlot, a whore, and even asked her if she’d ever seen a map.

Yet in the end he listened to her and took her advice. He had backed off the insecure comments and they spent hours relaxing in bed together where she gave him impromptu lectures about chapters from Roman history. For a man he wasn’t so bad.

Hope for his prompt return was now coursing through her, and not only because she missed him.

Ever since her spies informed her of the bishops’ plans, she had been terrified. If Sebastian were to die in battle, no one would protect her from these fanatical men.

How many years had she spent imagining that Ravenna would one day fall to a barbarian force? Now it seemed clear how foolish this had been: as she’d always known, Ravenna’s walls were enormous and supremely fortified. The people she should have been fearing this entire time were the people already inside the wall -- people like these bishops who showed up from the east with fanatical ideas about burning down icons and killing witches.

Would she even be safe in Constantinople?

Yes, she reminded herself, so long as she was empress. So long as Sebastian were there. By the time they’d installed themselves in Constantinople they’d surely have found some way to deal with the iconoclasts.

But the situation now was exactly as she’d often prophesied: the Empire was more than able to destroy itself. If she weren’t careful, she’d be killed by Byzantines right here behind the walls of Ravenna, a victim of a witch trial or assassination.

Daphne resorted to her lessons from history.

She knew that for many centuries Christian cities had periodically erupted into violence over the appointment of bishops. If she were to survive the challenge of these eastern churchmen, she’d need to harness that violence toward her own purposes.

She needed to pick a side and play the role of a devout Christian. This could keep her safe from witch trials and simultaneously convince the pro-icon priests that she was on their side: there was no side for a pagan, she knew, as there were hardly any pagans. She would only be safe if she could visibly convince people of her devotion.

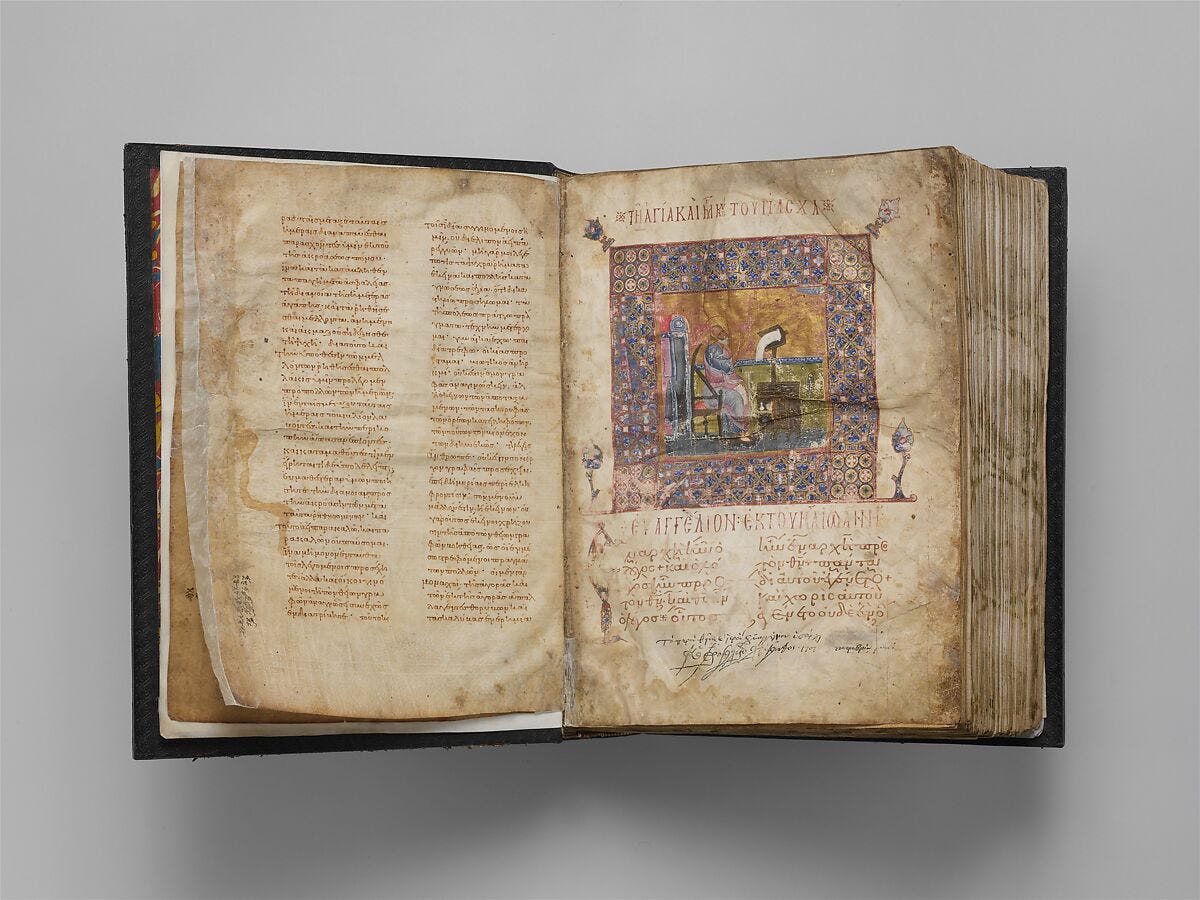

She procured numerous icons from shops around the city and spread them around her palace chambers as if she’d always prayed to Jesus and Mary and the saints. She even purchased books with illustrations of the Gospels to add to the deception. She had Sebastian’s most trusted guards build her a small altar on which she placed incense and candles and numerous pictures of Jesus, as if her chamber itself were transforming into a church. And she found that she liked this new environment around her, if only for the aesthetic of it. The bishops were right: she was a pagan by nature, and pagans thrived, she supposed, on the sensuality of worship. Soon all the servants thought of her as a devout Christian convert, devoted to her icons.

When she prayed, she pretended she was praying to her real goddesses — Athena, Aphrodite, Diana — and not to the image of Christ staring back at her from the icons.

After several days of preparation, she requested a meeting in the palace with the Archbishop Leo of Ravenna, the man who had baptized her, and maybe the only man she’d truly fooled from the beginning. The Archbishop Leo had glistened with pride upon baptizing and converting such a fallen woman.

She also knew he was in favor of icons. If she was ever going to make a move against the iconoclasts, she would need the Archbishop on her side.

Boldly, she received the Archbishop in Sebastian’s office, which he was letting her use while on campaign, and she filled the whole space with icons, incense, and illustrated gospel books. The map of the Mediterranean world stayed on the wall: a reminder, she thought, of the stakes. This whole empire — actively under invasion by barbarians from the north and Muslims from the south — might destroy itself over an argument about pictures. She knew that the Archbishop must be just as worried as she.

“Archbishop!” she exclaimed dramatically when he came into the room.

He remained standing. So she did too, but she kept moving, circulating between the icons as if in hysterical panic, and each time she began to speak, she interrupted herself with feigned tears.

“Archbishop!” she exclaimed. “Have you heard? They are coming for our icons!”

The Archbishop nodded sadly. She wondered if he’d dare speak against the emperor.

“What am I to do?” she asked. “I have only just converted to the Faith. My icons and my images bring me so much comfort and joy. I pray to them throughout each day. And now these wicked men have come to destroy the religion into which you brought me, Lord? There must be something you can do to stop these foreign men!”

The Archbishop Leo only nodded sadly. “It’s a terrible situation, Daphne,” he conceded.

“You are the Archbishop!” Daphne exclaimed. “There must be something you can do!”

“I am unable to stand up to the emperor when he has so many Isaurians now stationed in Italy,” the Archbishop Leo said. “You know the emperor himself is an Isaurian and these men from the east are extremely loyal to him.”

She shivered at the reminder. Two major Byzantine armies were now present in Italy: on the one hand was the predominantly Isaurian and Greek force led by a commander whom she’d yet to meet because he had been raiding monasteries; and on the other hand there were her husband’s forces, primarily composed of Italians and Illyrians. The first force was thought to be fanatically iconoclastic and the second force was thought to mostly be iconophilic. What would happen if these two forces began clashing in the streets of Ravenna? As she had often said, the Empire would destroy itself. No one had to sack Ravenna for Ravenna to fall.

“And yet, Archbishop,” she said to Leo, forcing herself to sound frantic with fear, “the Isaurians have gone on campaign in the countryside. They’re busy destroying monasteries! They’re destroying houses of God! They’re murdering monks. Do the city people not know about this? Something must be done to inform the people!”

Leo hesitated. He must have known what she was suggesting. “Some people know,” he said, “but most of those monasteries are very secluded. But of course people know. The Isaurians have destroyed some icons in the city itself, though not as aggressively.”

“The people should know what has happened to all these monasteries in Italy!” Daphne exclaimed. “Monks being murdered! Holy men of God being murdered! Please, Archbishop,” she knelt down before him and counted the beads on a rosary. “Please, Archbishop! You baptized me! This is my Faith and my Faith is being destroyed by these horrible people! You taught me in the Faith!”

Leo backed away. “I must go,” he said. “I am deeply sorry for what is happening, but there is nothing I can do,” and when he said this Daphne saw genuine fear in his eyes. This man was terrified to die; he was not willing to take risks even for his own Faith.

“Please! Archbishop!” Daphne forced a shrill sound into her voice. “Please!”

“I must go,” Leo said, and he rushed out from the office, leaving her with her incense and icons and rosary beads.

At least in any witch trial he could testify to the fervor of her faith.

As it was, Daphne dropped the act as soon as he was gone. “What a fucking idiot,” she muttered. “What a coward! Unwilling to stand in defense of his own religion! Unwilling to take action when monks in his own religion are being slaughtered!” No doubt the Archbishop only hoped to live out his life in peace.

Daphne’s spies would have a new goal now.

The listening was finished. The time had come to orchestrate the kind of crisis about which she had read so often in history books.

With both her husband’s force and the Isaurian force departed from the city for now, there was an opportunity for Daphne to strike against the bishops. The city guards, most of them devoted to icons, were unlikely to intercede if all went to plan.

Daphne’s Spies

Daphne’s two dozen spies fanned out across the city.

The spies slipped into taverns, tenement buildings, and churches, conversing wherever they went with the people, sharing rumors of mass slaughters of monks in monasteries outside the city. The people, who feared the Isaurians and had already seen some of them smashing icons in the street, became more worried not only for their own lives but also for their right to continue worshipping God in the ways they believed valid: through icons, through touch and scent, through the admiration of golden images of Jesus, Mary, and the saints.

The people in the streets were much braver than the Archbishop Leo.

They only needed to know just how determined the newly arrived bishops were to destroy their religion, and they would finish the job without Daphne leaving her room.

And Daphne, through her network of spies, made sure they did know.

Days went by: spreading rumors, working the people up, inciting fear in the population, all while Daphne sat in the palace receiving almost no visitors and waiting, waiting for the people to rise. To avoid suspicion of her involvement she met only with one girl, Lucille, her most trusted confidant from her theater days and a woman she promised to bring to Constantinople. Lucille then communicated her orders to other spies around the city.

Daphne knew the people of Ravenna: they were deeply devoted to their icons. Now that they had the appropriate information, and with most of the Isaurian soldiers gone, they could act exactly as she had imagined they would.

An old woman with an icon

Finally, one day, after a week of inciting the populace with rumors true and false, Lucille was walking through a central square where she saw an old woman holding up an icon by the fountain. The woman was wailing and crying out, demanding justice for the monks who had been slaughtered in the monasteries. City guards, posted around the square and loyal ultimately to Sebastian and the iconophiles, seemed uncertain how to proceed. In fact they did nothing; they themselves became an audience to the woman’s claims. Some of the guards even came forward to join the watching crowd.

“Hundreds of monasteries all across the Empire have been torn to the ground!” the old woman shouted. “Thousands of relics, icons, and precious images have been melted down for gold! And what does the Archbishop Leo do?” The woman paused. She was genuinely crying and a growing crowd had gathered to listen to her speak. “What does he do? Nothing. He allows the destruction to continue!”

Lucille lingered off to one of the thin roads emptying out into the square. She watched the crowd grow until several more women had joined in on the wailing around the fountain. All of them were now shouting pronouncements against Leo, the accusations escalating quickly: “He turns a blind eye to the murder of Christians! He obeys the foreign bishops from the east! He is possessed by a demonic force that enables his callousness in the face of the very people who murder the monks he should protect!” And then, finally, one old woman said that Leo must die.

The crowd erupted in approval. Soon the whole square was filled with the mob, and they were moving in the direction of the cathedral, following the old women as they hoisted icons in the air. The guards did nothing to stop them; guards even stepped to the side as the procession advanced.

Lucille rushed toward the palace to inform Daphne. Her friend would be extremely pleased. The archbishop and the eastern bishops were scheduled, Lucille was certain, to be in the cathedral at this very moment. And many of those in the procession were carrying glistening blades. They would start with Leo and then they would kill the other bishops. With luck, they would kill them all.

Sebastian and the Lombards

Soon after the Lombards appeared on the northern horizon, papal forces emerged from the ruins of Rome and began advancing toward Sebastian. Then the Lombards advanced as well. They faced a fight on two fronts.

They were effectively surrounded.

“Well,” Sebastian said, turning to his officer, “ready to die?”

The officer looked at him with fear in his eyes.

Sebastian cringed at his own pessimistic comment. He needed to display a confident presence now more than ever, for the sake of his men, many of whom were crouched into defensive positions with their shields. An enormous storm of arrows was soon flying at them from the Isaurians; most of his men caught these on their shields and several others dropped dead. He saw their bodies falling limp everywhere: on the edges of his lines and even in the middle.

“Shield wall!” Sebastian shouted. “Shield wall on all sides!”

The infantry fanned out, forming a circle of tightly intertwined shields which wrapped around Sebastian and a few other men on horseback.

“We should charge now,” Sebastian said to the officer beside him. “It’s the last thing the Lombards will expect.”

The men opened a hole in the shield wall through which Sebastian raced on his horse. He linked up with the rest of the cavalry, still in battle formation outside the circle.

“Charge!” Sebastian shouted. “Charge!”

With Sebastian at their head, the cavalry rushed across a field of grass toward the Lombards. Sebastian could clearly see the weakest point in the Lombard lines and it was toward this point, on the far right, that he led his men. Arrows struck a few of them as they advanced, men falling limp from their horses, and then Sebastian’s own army began shooting arrows into the Lombards.

The effect of the cavalry charge was immediate — the Lombards had not expected it and, poorly armored as they were, it was easy to see the fear in their eyes as Sebastian rushed closer and closer to their lines.

He was sure he would die in this battle, but this did not matter: he knew how to fight, and he would fight. Even so, to his surprise, the image of Daphne filled his mind. Her face shone more radiantly the closer Sebastian came to the Lombard lines and the closer he came to possible death, and for the first time in ages he felt what he used to feel in battle: fear. Fear that he would lose her because he would be dead.

The cavalry smashed head on into the weakest point of the Lombard lines. These people were cowards deep down, Sebastian thought, and poorly armored at that. He slashed his sword right and left: blood sprayed from necks and splashing across his face and horse. Metal clang against metal. Men screamed as they fell from horses and dropped dead in the grass. Some Lombard horses kicked and neighed in terror as the much more heavily armored Byzantine cavalry plunged swords into their rider’s backs, necks, and sides. All the while, Daphne’s image stayed in Sebastian’s mind.

He was afraid to die.

He’d hardly felt that in battle before.

But Daphne made him afraid to die.

He killed with more determination than he’d ever felt before. Dozens of Lombards fell to his sword, their blood drenching his face, armor, and hands.

Soon Sebastian and dozens of other cavalry men were behind Lombard lines. The Lombards’ supply camp was only some distance away; Sebastian could go for the women and children, forcing a retreat. But his infantry were surrounded: “Turn around! Attack again!” he shouted. He and the other cavalry began swerving back around to strike once more. They had already attacked and scattered one side of the line; now Sebastian led them in the direction of a weak point on the opposite side.

And as Sebastian charged, he saw in the distance the same Isaurian army he had thought to be raiding monasteries.

The Isaurians were storming down a hill against papal forces. His own infantry was now advancing toward the Lombards, whom he apparently now had surrounded.

“We are saved,” he thought, and then he smashed again into Lombard lines, killing and maiming.

Daphne had trained him well: even as he fought, the recesses of his mind contemplated the political situation. If the Isaurians took the pope prisoner, he could potentially avoid enraging Italy. He could blame the whole thing on the Isaurians who would be holding the bishop of Rome captive.

It felt better than ever in that moment to slice his sword through an enemy’s neck.

Once he and his fellow cavalrymen had broken through the line once more, they turned around to charge yet again, this time from the left, and at the same moment Sebastian’s infantry also reached the Lombard lines so that the Lombards began to rush away from the battlefield in panic.

Rarely had Sebastian witnessed such a swift change in fortunes on the battlefield.

“Power,” he thought. “Power, power, power,” and there was Daphne in his mind.

The Bishop of Rome

That night, after the battle, Sebastian’s men set up camp amidst the ruins of Rome. He allowed them all to steal whatever of value they could find in the decaying city, and after hours of pillage they were sleeping, chatting, and relaxing beneath the stars when Sebastian and the Isaurian commander, Trokandas, entered the papal palace and confronted Julian, the Bishop of Rome.

Sebastian had met Trokandas only once, briefly when the Isaurian army arrived in Ravenna, but the man had a reputation of a great warrior and the two of them got along immediately. Sebastian was thrilled with a successful battle in which at first he’d been so certain of death, and his mind was saturated with memories of Daphne whom he now knew he would indeed see again. He met several of the other officers among the Isaurians, many of them Greek, and his erstwhile annoyance with the Isaurians was severely tempered by the fact they had just saved his life.

Wanting Trokandas to take the man prisoner, Sebastian let the Isaurian do the talking.

“You made an alliance with the Lombards,” Trokandas accused, “which is confirmation enough that you are a traitor to the Empire in addition to being an idolater.”

“I am loyal to the Empire,” the pope insisted, although he usually ignored the imperial delegations that arrived in his city. “And if I am not, then what reason do I have to be disloyal?”

Trokandas gave out a short laugh. “The Empire stands against idolatry and other forms of pagan worship,” Trokandas said. “Whereas you live in a palace full of graven images.”

Julian snickered. “Ten years ago the emperor supported so-called ‘graven images,’” the pope said. “Just as virtually everyone in the Christian world did. Then the Muslims conquer more Byzantine lands and suddenly the emperor is against ‘graven images.’ And of course he’s against graven images at the very moment he needs more gold to resist the Muslims. Do you not realize what you are doing? You’re admitting that Christianity itself has been in error for centuries. We have cherished these images for hundreds of years. Has the Church been captive to a lie for all that time?”

Sebastian appreciated this point.

Trokandas seemed genuinely perplexed. “The Church,” he spat, “cannot be in error, and only a fool such as yourself could claim such a thing.”

Pope Julian continued, “very true. And if the Church cannot be in error, then it cannot be the case that the entire Christian world has been immersed in sin for all this time. You think you are standing up to Islam by winning some kind of purity contest against the Muslims, but what you are actually doing is conceding to the Muslims that Christianity has been in error. That’s what you are doing, Commander, when you spread across the countryside burning down monasteries. You are conceding to the Muslims that Christianity should be replaced by something like Islam.”

Trokandas looked at Sebastian for assistance. The man was, Sebastian thought, a simple soldier. He had probably never thought so deeply about the issue.

When Sebastian said nothing, Trokandas continued, “the Church is not in error,” he said, “but the people are, these people who carry forward pagan practices, the same kinds of pagan practices which the Muslims are eviscerating from the face of the Earth. The Empire is God’s vehicle in the world, and if the Empire is losing land to the Muslims, it must be because the Empire, not the Church, is in error. Although,” Trokandas said confusedly, “it could be that people in the Church are in error. Such as yourself. And that is why we are purifying this peninsula of idolatry.”

Sebastian stifled a yawn. Trokandas was going to do it: he was going to arrest the pope first so that Sebastian could wash his hands of the whole affair.

“You are to come with me,” Trokandas said, “back to Constantinople, and there you will answer to the emperor for your crimes against God and Christianity.”

Sebastian nodded along. The last thing he wanted was the pope as his prisoner.

“You are under arrest, Julian,” Trokandas said.

The pope shrugged and Trokandas’s soldiers took him away.

Sebastian thought that Julian was a very brave man.

As Sebastian fell asleep beneath the stars that night near the ruins of the colosseum, he thought of all the past attempts by Byzantine armies to capture Rome. So many had failed. Thousands had died over the centuries in various attempts. And now he and Trokandas had taken the city like it was nothing.

No doubt this was thanks to Rome being so much less populated, so much less wealthy, so much more poorly defended than in the past. Still, Daphne was right: there was glory in this, and Sebastian was fine to share it with Trokandas.

But he knew what Daphne had warned him about Italy and the same applied to Rome: they would not hold Rome. How could they? The needed to return to Ravenna and did not have the manpower to leave a substantial garrison in the city. They would return to Ravenna and leave Rome to its own devices.

Archbishop Leo in the Cathedral

The Archbishop Leo was in the cathedral with the eastern bishops, the idiot Konstantinos at their head. He hated these men and what they were doing: they had thrown all the commoners out and, under armed guard meant no doubt for the Archbishop, the eastern bishops were now showing Leo all the art on the walls that must be painted over or destroyed. Every icon, every hint of incense, every speck of gold must leave this cathedral, leaving the place bare and desolate so that worshipers could avoid the temptations of idolatry when they were gathered to praise the Lord.

Leo was genuinely horrified, but what could he do?

He could not appeal to Sebastian while the Commander was away on campaign. Daphne might support him, but what did she matter? She was a hysterical woman with the zeal of a new convert, Leo thought, and all she could do was cry in her bedroom. No doubt she felt guilty for the many sins she had committed in her theater. Then again, perhaps she was right: now was the time to make a move. The Isaurians were also on “campaign” — by which they meant the destruction of every monastery they could find across northern Italy — and Leo might be able to stand up to these men without fearing for his life. Maybe.

But Leo was a man who deeply valued his life. Leo was not willing to take the slightest risk when he was an old man who only had a few years left to enjoy the world. Deep down, he was not even sure if he truly believed in the afterlife, and he could not think of anything he cherished more than being alive. He knew all about the martyrs; he had no desire to be one. To hear the birds chirping, to look at the hills of the countryside, to lay eyes upon a newborn baby, to admire the body of a woman: these were the little things that kept Leo going. He’d given his whole life to God and had no family of his own, but he loved the people of this city, loved the chance to baptize and bless them and support them in the Faith, if only to help them find joy in life.

“Best to do nothing,” Leo thought to himself. “Best not to interfere.”

And yet he also loved the icons, relished the scent of incense, cherished the illustrated Gospel books stored in this cathedral and in churches all over the city. What Leo truly loved was art. And these men seemed bent on destroying all art. But again, what could Leo do? He was an old man without an army, and Sebastian had never shown an inclination to use his army against the bishops. How could he? These men had been sent by the emperor. Leo submitted to Fate.

Once the bishops were finished showing Leo all the art that must be destroyed, Leo followed them meekly toward the doors to depart the cathedral. The foreign bishops whispered excitedly among themselves; they were ravenous to see art destroyed, Leo thought. “But then why live at all?” Leo wondered.

“What is that?” Konstantinos asked, raising a hand and stopping the others. “Shh!”

They went silent and listened. A crowd was roaring, and the roaring was drawing near.