Malta and the Celebration of Christian Nationalism (October 19, 2022, the severed branch)

In Malta, I found a country with a national identity rooted in its history as a "frontline state" in the old Mediterranean struggle between Christianity and Islam.

world history: all my links in one place ! 💖⭐️🌟💫💗💞🧙🌍🌏🌎

Proceed chronologically or start with any topic!

next:

the early capitalists turn west: genoa, the demonic nature, and the end of christian domination over the mediterranean sea (christopher columbus targets the western region)

I went to Genoa thinking about the sea, but I found a city cradled by fortress-strutted mountains (all photos my own)

A street in Valletta at sunset (photos my own)

Sources:

Carmel Cassar, A Concise History of Malta

The Inquisitor’s Palace Museum (Birgu, Malta)

The Museum at St. Paul’s Cathedral (Mdina, Malta)

General Opinion Survey of the Maltese Population 2021

I arrived in Valletta, the capital of Malta, knowing very little about the tiny country, having never really planned to visit. My awareness of the nation stretched back to middle school, when my partner in geography class repeatedly expressed his extraordinary pride in being Catholic and Maltese. But I find that education is one of the greatest benefits of travel, and I went to Malta precisely because I knew almost nothing about it. Once I arrived in Valletta for five nights on that small Mediterranean archipelago of 525,000 people, I quickly purchased A Concise History of Malta by Carmel Cassar. I was soon enthralled and disturbed by the complex historical developments of Maltese identity and nationhood, which are deeply rooted in the old crusading and inquisitorial mentalities of Christianity. My old companion’s obsession with being Catholic suddenly made more sense; in his mind, it perhaps could not have been separated from being Maltese. Although Malta does not horrify me in the way the Byzantine Empire does, a strident Christian worldview nevertheless lurks in its museums and in its culture, one which unapologetically defines Malta as a Christian nation in a Christian civilization with little room for religious diversity.

Valletta lies nestled between two networks of natural harbors, each of which was long secured by a system of fortresses. The most important of these is probably Fort St. Angelo in Birgu, just across the small bay from the capital. It was there where the Grand Master Vallette of the Knights of St. John, an organization which ruled Malta for over two centuries as their private fief, commanded the forces defending the island from an epic assault by the Muslim Ottomans in 1565. Strolling through Valletta on my final day, I lingered beside St. Angelo’s counterpart at the base of Valletta, Fort St. Elmo, and I imagined the scenes of battle from that savage summer. The Knights, and the European monarchs who supported them, saw themselves as fighting on the frontline of a centuries-long struggle between Islam and Christianity. At the expense of the thousands of Turkish soldiers thrown to their gruesome deaths in repeated assaults against the fortress’s walls, the fall of St. Elmo to Ottoman forces was one of the first outcomes of the Siege of Malta, a moment with heavy significance for Malta’s national identity even almost five hundred years later.

Having learned about that great siege in A Concise History of Malta, I gazed across the bay and imagined Grand Master Vallette’s hopeless struggle to resupply and communicate with the frontline base across the bay. At some point, once the Turks had completely surrounded St. Elmo, he made the decision to cut off supplies to the fortress, and the few who survived the final Ottoman onslaught swam for their lives across the water to St. Angelo. Over another month would pass before Vallette’s forces narrowly prevailed and the Ottomans finally retreated. A few years would go by before the women and children evacuated to Sicily would feel safe enough to return to Malta, from which they had been evacuated. In the meantime, Vallette founded the new capital of Valletta, and he became a celebrity among the Christian monarchs of Europe. As the man of the hour who had secured a tiny but strategically crucial island, these kings and queens viewed him as having saved the central Mediterranean from Muslim domination. The Knights, all of whom were foreigners reigning over the local Maltese peasants and meagre notables, would continue to rule Malta for another 232 years after the siege, building it up into a naval power to be reckoned with. The Knights’ navy, based in the harbors around Valletta, was an essential contributor to the various alliances formed between Christian powers, including Venice, Genoa, Spain, and Sicily, in the many struggles to come against Muslim forces. As Cassar explains, the memory of Malta’s place in that conflict undergirds its identity today.

Fort St. Angelo in Birgu, just across the small bay from Valletta

Of course, I don’t want to paint an unrealistic picture of piousness. Strolling through the streets of his namesake capital now, the ubiquitous ungodliness would surely move Vallette to violence, just as one Grand Master’s attempt to ban prostitutes from Valletta inspired insurrection among the supposedly chaste and Christ-fearing Knights (Cassar). Multitudes of prowling tourists drive the unholy debauchery which rules the streets throughout the modern night. Malta, a country with very limited natural resources of its own, has always depended on foreign investment and food imports to sustain and grow its population. Today, almost 13% of Maltese GDP and almost 15% of its employment depend on the tourists who flock there. Some arrive to learn English at its particularly cheap English language schools. Others come merely to drink, vape, fornicate, and relax on party boats or beaches. Regardless of the motives which bring them there, the streets of Valletta and neighboring Sliema are overflowing with foreign and native revelers who could not care less about biblical sexual precepts, especially not after dark. Vallette and the inquisitors who ruled Malta would no doubt have put some of them to death.

But in the absence of these saints, the appeal of English-speaking Malta as a hedonistic party destination for beefy British men and half-naked couples is clear. My friend and I took a boat tour that brought us beside several stunning caves and pristinely blue and secluded bays, each of them ideal for swimmers and sunbathers. At one point, our boat passed by a small rocky island with a large statue of the Apostle Paul facing out to the sea, but we did not linger there. No doubt to the horror of the curators who designed some of the more theocratic exhibits in the museums I visited, including one which glorifies the missionary role of the Roman Inquisition in Malta, northern European vacationers could be forgiven for leaving the country without any idea of just how central Christianity has been to its national identity.

The mythology of this identity goes back almost 1500 years before the great Siege of Malta. Maltese national legend asserts that Malta is the world’s oldest Christian country, tracing its Catholic culture all the way back to the Book of Acts in the New Testament. The Apostle Paul shipwrecked there on his way to Rome in AD 60, and Malta imagines its devotion to Christ beginning at that moment, even dating the first Bishop of Malta to that time. Hardly any of this can be verified beyond the Scriptures. Nevertheless, a large statue of St. Paul is positioned on a tiny island in “St. Paul’s Bay,” and Maltese Christian nationalists have adopted dramatic imagery of the apostle as the symbol of their country’s core identity as a “frontline nation” (Cassar) within Europe and “Christendom.” As Cassar suggests, the heavy emphasis on Chrisianity is partly a way of reconciling Malta’s indigenous Semitic language, heavily related to Arabic, with its “European-ness,” which still seems to demand Christianity as a prerequisite. The very first display in the museum at St. Paul’s cathedral in Mdina, prominently displayed before the ticket booth, drove this point home for me in startling language. The proclamation begins with a nod toward tolerance, but it ends with an emphatic Christian declaration of Maltese, European, and Western identity.

“There are many roads to God. They are called religions. In Malta and the rest of Europe most people have traditionally followed the religion of Christianity…. As a Cathedral Museum, we are a Christian foundation in a Christian country…. Christ’s moral teachings are not only compelling but also conducive to a good life on earth, both for each one of us individually and for society as a whole…. These were revolutionary teachings that came to form the basis of western civilization and democracy. They are the fundamental values that made European society among the most caring in the world.” (Museum at St. Paul’s Cathedral, Mdina)

It is a strikingly unreflective language from a religion which spread throughout Europe, Africa, and the Americas through the violent eradication of indigenous traditions and cultures. It struck me as demonstrably absurd o describe European society, which enslaved and massacred people in regions all over the world, as “among the most caring in the world.” And to credit Europe’s supposedly “caring” disposition to a religion which justified centuries of crusades, anti-semitism, and colonialism was even more discordant with the world history I have read. I hardly need to belabor this obvious point. But the perspective of the museum at St. Paul’s cathedral made it easier for me to understand the celebration of the Inquisition which I encountered at the museum in the Inquisitor’s former palace in the old capital of Birgu.

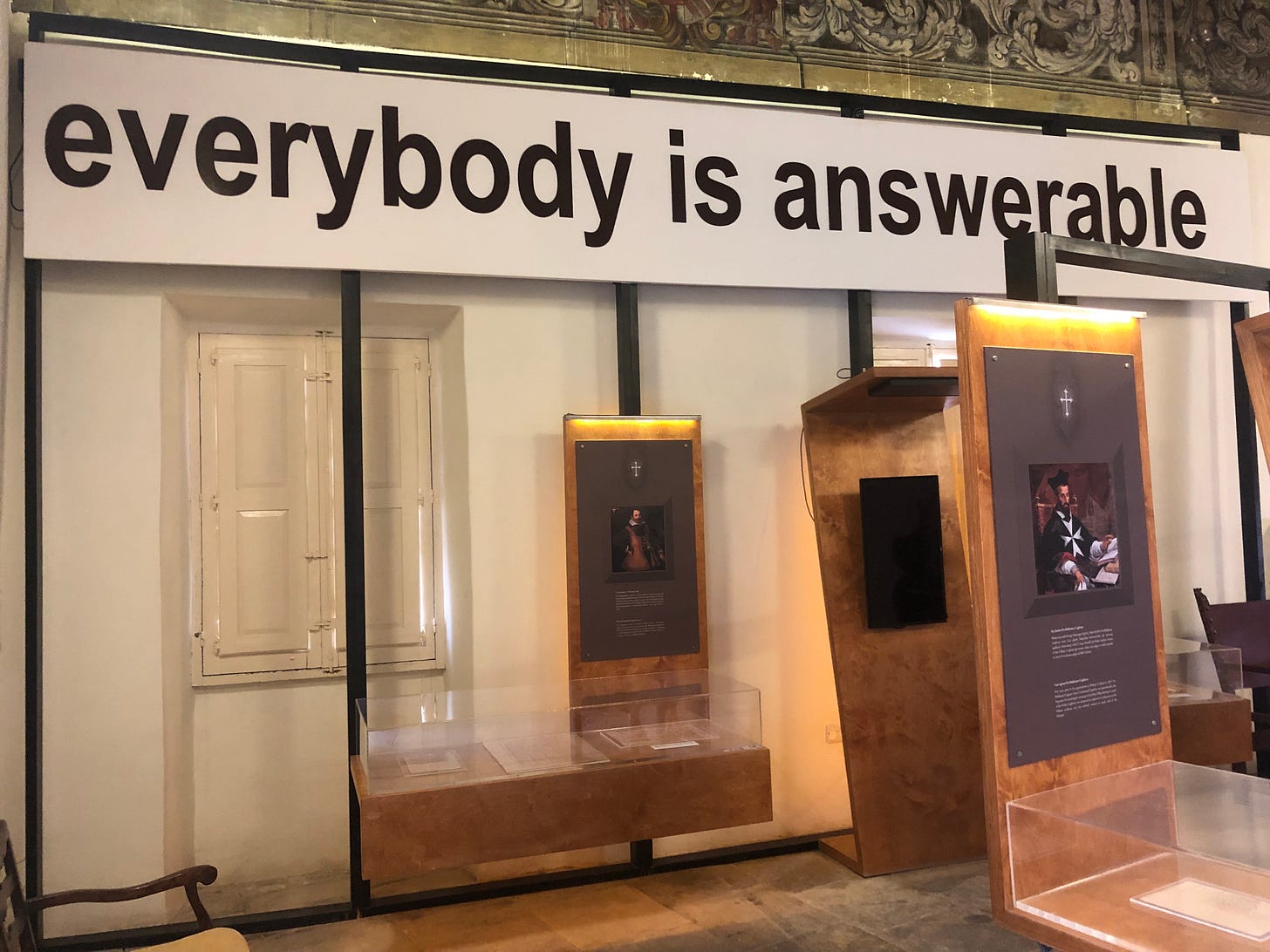

The Inquisitor’s Palace today celebrates the inquisitors, two of whom became popes

The Inquisitor’s Palace was the first museum I passed through in Malta, and the underlying tone was unquestionably one which defended that terrifying institution as ultimately a good thing for “society as whole.” In fact, it is precisely the crucial role of the inquisitor in ensuring that the Maltese people became better Christians which the Inquisitor’s Palace Museum cherishes today. The inquisitors, who held papally ordained jurisdiction in Malta from 1574 to 1798, when the Emperor Napoleon banished them, were not generally Maltese. But the people of Malta apparently have cause to be grateful for the guidance they provided in graciously teaching them the errors of their ways. As one exhibit in the Inquisitor’s Palace puts it, “most people did not realize the seriousness of their actions until their Confessor insisted they should denounce themselves to the Inquisition.” The role of the inquisitor was not to oppress, torture, or murder people, but rather to ensure that Christ’s flock in Malta, which included virtually everyone on the island, would grow into the good Catholics they were meant to be. “Every now and then,” reads one exhibit, “the Inquisitor would feel the need to issue an edict thereby reminding people of their obligations as good Catholics and the punishments incurred by those who did not do so.” The apparent crimes outlined in these edicts included becoming a Muslim, owning banned books, practicing love magic, and engaging in “heretical” speech. At no point does the museum even subtly suggest that the eradication of these “sins” was not justified.

Instead, the museum defends the inquisitors and celebrates the outcomes of their office. If the museum does not outright defend torture, it is quick to assure its visitors that the inquisitors were “reluctant” to use torture, and that torture was only “reserved for cases of very serious breaches of orthodoxy, when it was overtly clear that those accused were lying in the face of evidence, or that they were refusing to reveal all they knew.” As examples of cases where the merciful inquisitors found themselves obliged to resort to tormenting their suspects, the museum lists “the owning of prohibited books” by a silversmith in 1575, the practice of “love magic” by a 50-year-old woman in 1619, the utterance of “prohibited blasphemy” by a young Sicilian man in 1636, “apostasy to Islam” by a French sailor in 1641, and several cases including “heretical talk” and “sorcery.” By rooting out such “very serious breaches of orthodoxy,” while using torture only when absolutely necessary to get to the truth, the Roman Inquisition in Malta fulfilled its godly mission as described by the museum:

“The Inquisition took it upon itself to communicate the truth, fight ignorance and heresy in order to convert the ordinary folk to the Church doctrine as propounded by the Council of Trent [1563]. By inducing people to act as good Catholics, the inquisitors acted as missionaries. They emphasized the need to teach the basics of Catholic Reformation through pastoral work…. The more spectacular side of the missions was evidently to impress a public whose mentality had had retained its country roughness and who could learn most quickly from a direct, simple approach to religious teaching…. The fear of God which resulted was designed to lead the faithful to a general confession and to receive holy communion.”

The Inquisitor’s Palace praises the inquisitors for going after both high and low

The Inquisitor’s Palace Museum ends with a comparative exhibit showcasing Maltese Christmas traditions side-by-side with other nativity scenes and practices from other Christian-dominated countries. By then, the museum has also honored the achievement of two inquisitors in Malta who went on to become popes. At one point, the museum lauds the career of Saint Peter the Martyr, apparently the “Patron Saint of the Inquisition.” After being raised by parents who adhered to the Catharist heresy, which was popular in France and northern Italy, he went on to become an inquisitor in Milan in the mid-1200s. There, “he focused his efforts on the eradication of Catharism” before being murdered in 1252 by a “Milanese heretic.” At no point does this particular display mention the brutal crusades and mass killings of Catharists in France and elsewhere, which the Catholic Church eagerly promoted in the thirteenth-century. Instead, it maintains positive imagery of “Saint Peter the Martyr” and proudly notes the date of his liturgical feast and a Maltese chapel dedicated to him.

From start to finish, the Inquisitor’s Palace Museum takes on a grateful and uncritical tone toward the inquisitors and their mission, whose means were always justified by the end of creating a more perfect Christian society, and who only tortured people when they were “certain” the person was lying. And yet the very examples of crimes and offenses which the museum provides betray an utterly detestable program of theocratic totalitarianism, one designed to vanquish from Malta any thought or deed which contradicted the rigid decrees of Canon Law. Yet this is precisely the awful agenda which today’s curators are unashamed to celebrate. The ultimate result, the museum explains, was the welcome spread of standardized Catholic rituals and values across the Maltese island and archipelago. In the end, one exhibit concludes, the work of the inquisition and its missionary partners “brought about a change in the attitude of the faithful to communion and confession.” And yet how intriguing to contemplate that the Inquisition was apparently so necessary for an island which, according to the nonsense myths of Maltese nationalists, has been continuously Christian since AD 60!

Cliff views near St. Paul’s Bay, where the Apostle supposedly shipwrecked in AD 60

As I learned reading Cassar’s A Concise History of Malta, the mythologies of Maltese Christian nationalism run in sharp contradiction to historical reality. Under the Roman Empire, Malta was grouped together with the province of Sicily. In the centuries after the Western Empire’s collapse, the island passed between various rulers including the Byzantines until it was conquered by the Arabs and ruled by Muslims between 870 and 1091, at which point it was conquered by the Christian Normans. According to Maltese legends which developed in the sixteenth century, Malta retained a thriving but heavily persecuted Christian community during those two centuries of Muslim rule. The Muslims supposedly inflicted constant and brutal suppression of the Christians during that time. Once the Normans landed in Malta, myth has it that they were greeted by grateful Maltese Christians who were finally liberated from their Islamic tyrants. In reality, other than the Christian slaves whom the Arabs captured from around the Mediterranean and sometimes brought to Malta, there was virtually no Christian community at all in Malta during those centuries. Christianity as a religion essentially vanished from the island, while migration patterns make utter nonsense of the existence of an ancient Maltese “people.” And the Maltese themselves, speaking a language variously described by outsiders as an Arabic dialect, were actually devoted followers of the Prophet Muhammed. But historic Maltese nationalist circles would consider these realities to be deeply offensive. They have preferred the fantasy of continuous Christianity among a coherent Maltese people with roots in the first century. The hyper-religious, Catholic aspect of Maltese nationalism has its origins in the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem.

The statehood of Malta begins in history only with the arrival of the crusader Knights of St. John, a Catholic international order with medieval origins in a fanatical Christian outlook. Founded within a crusader state in Jerusalem in 1099, the Order of the 21st century retains embassies today in numerous countries, although it currently possesses no territory. Just this week, I was surprised to walk by the Order’s local headquarters and embassy in Vienna. Operating today as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, this “sovereign entity” maintains diplomatic relations with 112 states, holds recognition from some as a sovereign state in its own right, issues diplomatic passports, operates hospital trains in Europe, and deploys medical military units embedded within the Italian army. In 1530, the Knights of St. John, whom Muslim armies had first driven out of Jerusalem and then out of Rhodes, were granted Malta as their own private fiefdom in 1530 and tasked by the Church with the duty to defend it from Muslim onslaught. At the time, the Knights’ members included wealthy nobles from Spain, Italy, and France. The organization already held vast properties and investments all over Europe, deploying far greater wealth than the peasants of Malta. Cassar’s book is my main source for understanding the Knights in Malta at that time.

The Knights elected a leader for life, the “Grand Master,” and he acted in Malta as a near-dictator. He ruled over the local Maltese, who spoke an Arabic dialect and had extremely limited say over the workings of the largely Romance-language speaking Knighthood controlling the island from their increasingly wealthy ports. True, there were some local institutions involving Maltese notables, left over from the Norman days when Malta had been a part of the Kingdom of Sicily. And these authority structures did strive now and then to hinder or counterbalance the Grand Master. But the Grand Master not only controlled the military. He also had the backing of the Catholic Church, and numerous European monarchs saw him and his Knights as an essential bulwark against the expansion of Islam in the Mediterranean. As simultaneous religious and military leader, he was in practice answerable only to the Pope, the foreign monarchs who aided him, and to some degree the Knights who had elected him. Under the rule of the Grand Masters, Malta developed into a naval force to be reckoned with, and the current capital of Valletta was founded as a harbor town which controlled the distribution of food imports to the interior peasants. With some complexities and exceptions in practice, Malta under the Knights was characterized by the opposing dichotomy of an underdeveloped rural interior of impoverished Maltese speakers on the one hand, and the rich foreign merchants and soldiers speaking Italian and managing the economy from the harbor towns on the other. The Knights ruled over Malta until the Emperor Napoleon banished them in 1798.

Jean de Vallette, Grand Master during the Siege of Malta and founder of Valletta

One would think that that the Maltese would come to resent the the Knights of St. John and the Catholic Church which backed them, but developments were more complicated. Yes, as Cassar explains, there was always some level of opposition to the Grand Master. But the first seeds of Maltese nationhood were sown not by opposition to the Knights, but rather by the dramatic coming together of Knights and Maltese during the Siege of Malta in 1565. Having besieged Vienna just 36 years before, the Muslim Ottomans had Christendom on the defensive, and Malta became the new frontline in the conflict. Given Malta’s strategic location as a fortified island in the middle of the sea, what was at stake was whether Christians or Muslims would control the central Mediterranean. From May 18th to September 11th of 1565, brutal battles raged in the harbors around modern Valletta between the Knights and the Ottomans, who only failed to conquer the island due to a few crucial strategic errors. The Ottomans had already attacked a couple times before, and the Knights had spent well over a decade building new fortresses and upgrading old defenses. These held strong in the siege, after which the Ottoman navy was forced to retreat before winter to Constantinople. The battles, as Cassar describes them, were ruthless. After they had captured Fort St. Elmo, the Ottomans mutilated Christians’ bodies and tossed the mangled corpses into the water so that they would wash up at the base of the enemy’s forts. The Grand Master, commanding his men from his headquarters across the bay in Fort St. Angelo, ordered every Muslim prisoner killed and fired their heads at the Turkish frontline. When the Knights narrowly prevailed, they were celebrated by Christian monarchs all over Europe, and the whole conflict became central to the mythologies of Maltese national identity as a frontline state against Islam. Many Maltese museums accordingly glorify their old foreign rulers to this very day.

As Cassar explains, the siege won the Knights much more support from the local Maltese. They came to understand themselves as religiously united with the Knights against a common Muslim enemy. Nationalism, language, and ethnicity simply did not matter so much as did religion. According to Cassar, it was then that Malta’s conception of itself as a crucial frontline state in the wars between Islam and Christianity really began to develop, and it would carry this understanding forward into the 19th-century era of nationalism in Europe. Because of this, the myths of Maltese nationhood are tied up not into resistance against the Knights, but rather into the defense of Malta and Europe from the Muslims.

As the Knights’ rule progressed, Cassar shows how the Maltese progressively developed an elaborate mythology that they had been continuously Christian since the Apostle Paul arrived in AD 60. Their resistance against Islam did not begin with the Siege of Malta, they thought, but rather with Arab rule from 870 to 1091, when Maltese Christianity valiantly survived underground despite savage persecution from its Muslim overlords. This fiction was useful to Maltese notables, who used it to argue for more influence and power within the context of the Grand Master’s domination. It is not only the Knights, they could say, who have been steadfast Christians and defenders of the faith; we too, the indigenous people of Malta, are an integral part of the grand project of Christendom, with such an ancient pedigree that we are in fact the oldest Christian nation, and this gives us a right to participate in authority. Far from being inspired toward resistance against Catholicism by the domination of the Knights of St. John, then, the Maltese formed their earliest concepts of Maltese national identity around the religion of their foreign rulers, and war against Islam was crucial in that story. Even today, it is Malta’s role in defending Europe from Islam which helps shape its national identity, and it becomes easier to understand why Maltese museums are so eager not only to proclaim the country’s Christian identity but also to defend or even celebrate the Inquisition. As Cassar suggests, perhaps it is even precisely because the Maltese speak a language so closely related to Arabic that they are so eager to emphasize their Christianity and the Siege of Malta, each as evidence of their unequivocal membership of Europe, conceived within Mdina’s St. Paul’s Cathedral as a fundamentally Christian civilization. Certainly, the Arab character of Maltese history and language does not seem to be something which Malta strives to emphasize.

Instead, as one could easily predict, the Maltese have particularly hostile and skeptical attitudes toward immigrants and refugees compared to the European average. A report by the University of Malta in 2021 outlined the following findings:

“Data from a 2012 Eurobarometer survey found that Maltese individuals were significantly less likely to consider migrants as contributing towards the country; Only 32% of Maltese respondents thought that immigration is economically or culturally enriching for Malta, compared to the European average of 53% (European Commission, 2012). The survey also revealed that 41% of Maltese respondents would not like to have an Arab as their neighbor, and 63% would advise their children against marrying an African migrant.

A more recent version of the same Eurobarometer survey revealed that 51% of Maltese respondents feel uncomfortable with at least one type of social relations with immigrants, such as having an immigrant as their friend, neighbor, or manager (European Commission, 2018). Maltese respondents were also among the most likely to consider immigration from outside the EU as more of a problem than an opportunity for the country, with 63% agreeing with this statement, compared to a European average of 38%.” (General Opinion Survey of the Maltese Population 2021)

These attitudes are ironic given that the island has seen relentless patterns of immigration and emigration for the past two thousand years. As so often with 19th-century nationalist constructs of imaginarily cohesive “peoples,” it’s hardly even clear what a Maltese person is from a “peoples” perspective, especially after millennia of movements between Malta and Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. Life on the island for centuries was rough, with frequent famines stemming from the soil’s limited fertility, and food challenges frequently pushed people out before the situation improved and could draw others back in. According to Cassar, there was even a point in the centuries after St. Paul’s alleged shipwreck where the island, supposedly connected to the Apostle by an unbroken sacred chain of generations, was virtually completely emptied of its entire population. When people were there, population mixing was frequent, whether during Roman, Byzantine, Arab, and subsequently Norman/Sicilian rule. Or even during the days of the Knights, when merchants and workers from all over Europe came to Malta for the opportunities provided in its thriving naval harbors, and when Muslim slaves captured by the Knights’ navies were transported there. Perhaps it is this very instability which leaves Maltese nationalism clinging to two crucial cultural components - Catholicism and the Maltese language.

A street view while wandering around in Valletta

The final formation of Maltese national identity, as rooted not only in Catholicism but also in the Maltese language, came to fruition under British rule, which Cassar describes in detail. Of course, some might wonder if Catholic cultural and legal control over Malta diminished during 150 years of Protestant British control from 1813 to 1964. The British knew, however, that it was Napoleon’s targeting of the Catholic Church’s power which inspired the masses to quickly revolt against him. This was a strategic mistake which the British avoided, despite ample demands from within British society to put an end to Catholic idolatry in Malta. Instead, as Cassar puts it, the British hoped to maintain political control over Malta by whatever means necessary. To avoid upsetting the “natives,” they tolerated the power of the Catholic church over society. Hoping to avoid discontent and revolt, the British let the Catholic Church have free rein over education and other social institutions, including marriage. When the British attempted to grant authority over mixed marriages between Catholics and Protestants to civil rather than Church law in Malta, the Maltese were outraged by London’s encroachment upon the Church authority they so cherished reigning over them. So the British quickly backed down, leaving Malta as an exception to this law within their empire. But one area where the British eventually did become more assertive was in terms of both the Maltese and Italian languages, which had until then been dominant in Malta.

For the first several decades of colonial rule, the British took a tolerant approach to the Italian and Maltese languages, each of which largely prevailed on the island. But the situation changed in the second half of the nineteenth century. Thanks to the construction of the Suez Canal and the new possibility of the British reaching the colony of India via the Mediterranean, Malta became even more strategically important to British imperial strategy. The island was reborn as the headquarters of Britain’s entire Mediterranean fleet. Meanwhile, powers such as the newly unified Italy and Germany were on the rise. The sudden emergence of the new Italian nation-state combined with the presence of Italian nationalists in Malta to frighten Britain that Malta, so close to Sicily, could break away and form a part of Italy in the event of a conflict. Britain, which had once felt utterly secure in its complete dominance of the seas, became more fearful and paranoid about the threat these new forces posed to its position and possessions. In order to inculcate more loyalty among the Maltese to England, the British rulers decided to favor English in the offices of state and within the educational system. Several British officials worked to promote the Anglicanization of the Maltese people, hoping to make them “as English as possible.”

Since the entire economy and virtually all employment revolved around the needs of the British navy and administration, English was easy enough to promote. While it succeeded in largely displanting Italian, and while its legacy lasts today in the form of seemingly everyone in Malta speaking fluent English, linguistic heavy-handedness by the British had the additional effect of inspiring a Maltese nationalist movement organized not only around the role of the Catholic Church in society but also around the preservation of the Maltese language. In their paranoia about Mussolini’s Italy conquering Malta, the British even favored Maltese over Italian, and the working classes of Malta, who had often resented the Italian of the middle and upper classes, eventually went along with the program. When I was first heading to Malta last week, knowing very little about the country, I was not sure whether to expect the Maltese to speak much Maltese or whether it would be more like Ireland, where one hardly ever hears the old indigenous language except in a few select regions and settings. Instead, I regularly encountered and heard the Maltese language being spoken between Maltese people. The preservation of the local language in the face of British colonialism was one happy element I encountered from Maltese history.

the early capitalists turn west: genoa, the demonic nature, and the end of christian domination over the mediterranean sea (christopher columbus targets the western region)

I went to Genoa thinking about the sea, but I found a city cradled by fortress-strutted mountains (all photos my own)