the rise of religious totalitarianism in the eastern roman empire: a culture reborn in a demonic womb (a nation conquered by identity drones)

the transformation of rome from oligarchic republic to nightmare theocracy demonstrates the capacity of nations to be reborn into demonic wombs and emerge into a hell of their own making

world history: all my links in one place ! 💖⭐️🌟💫💗💞🧙🌍🌏🌎

Proceed chronologically or start with any topic!

Next:

the rise of religious totalitarianism in the former western roman empire (the construction of the catholic church, papal power, and modern catholic rituals)

for what happened in the Eastern Roman Empire:

Sources

J.M. Roberts and Odd Arne Westad, The Penguin History of the World

Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

Gore Vidal, Julian

A.D. Lee, From Rome to Byzantium

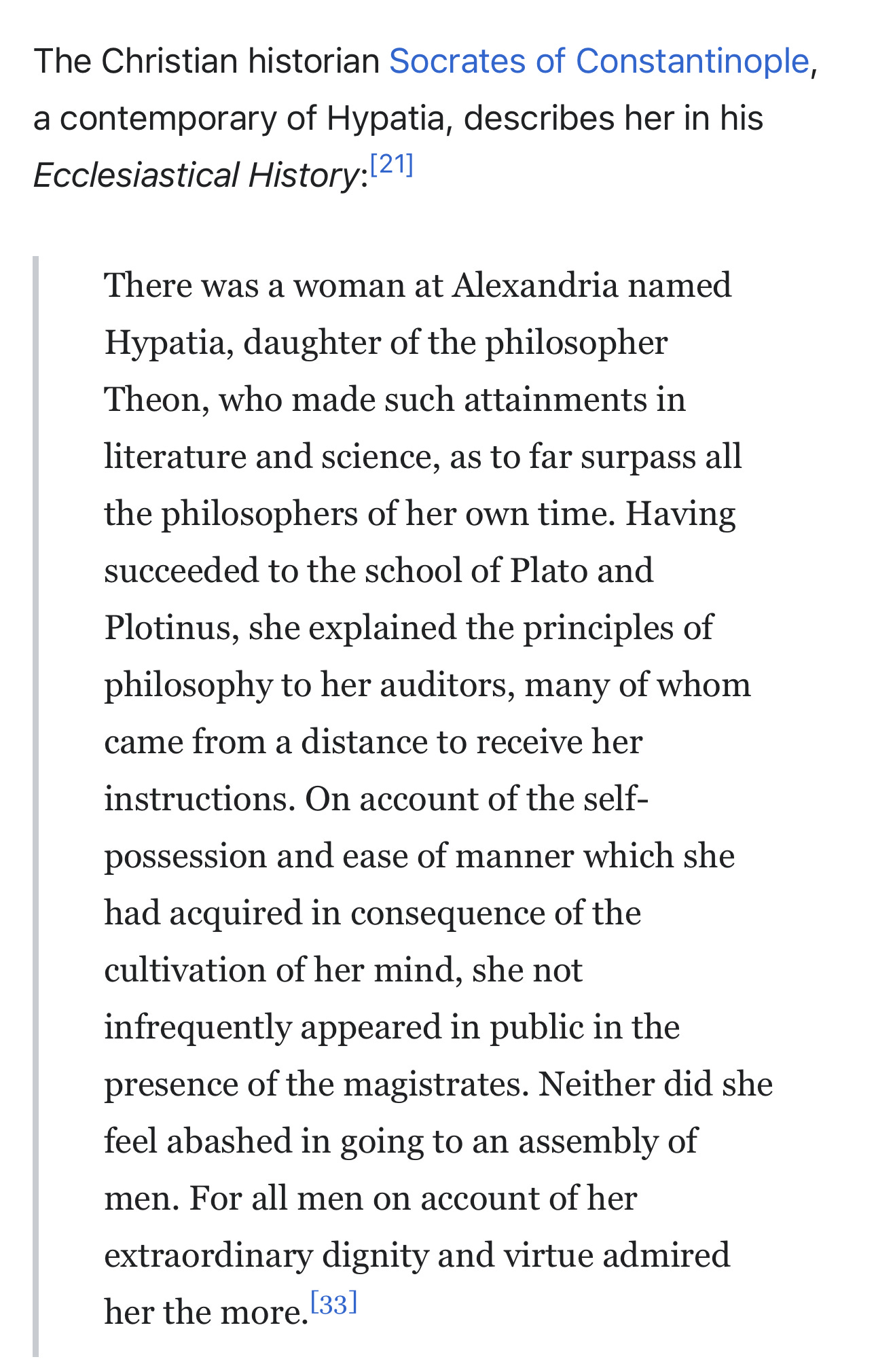

Long ago during grad school, in the dim light of an attic apartment, I encountered several volumes of Byzantine history. I had long been interested in Eastern European history and, theoretically, in the Eastern Orthodox religion. Ever since I had stood in the magnificence of Hagia Sophia, I had longed to learn more about the great people who built it. But now, as I gazed upon these hardbound books about the Byzantines, my acquaintance made a casual joke about an eighth-century Byzantine religious controversy about which I knew nothing. When she easily name-dropped the emperor behind the first wave of iconoclasm, a thousand years of mystery confronted me. I was swept away by a dizzying confrontation with my own ignorance. Still, I dared not ask any questions, lest I betray the vast emptiness which I now felt inside my brain. How much I had to learn, I thought, from a study of the mysterious Byzantines!

I knew I would never be able to take myself seriously as a complete human being until I had learned all about the Byzantines. For years, those erudite people had repeatedly brushed by me, but I had never devoted myself to understanding them. When I had crossed from Catholic to Orthodox Europe during my travels, I had been conscious of a civilizational boundary stretching back to the division of the Roman Empire into two halves, one centered upon Constantinople and the other upon Rome. I was dimly aware that, once the Western Roman Empire came to a formal end in 476 AD, its space gradually transformed into a Western Europe which the Catholic bishops of Rome sought to dominate without the interference of the distant emperor of Constantinople. The Eastern Roman Empire, meanwhile, continued as an entity until the Ottomans conquered Constantinople in 1453 AD. And it was within its borders, as well as its surroundings, that Orthodox Christianity spread. It was this Eastern Roman Empire which we now call the “Byzantines,” although they called themselves Romans until their final stand against the invading Muslim armies. But beyond these most basic contours of European history, I hardly knew anything about the Byzantines.

In Istanbul, I had stood inside the Hagia Sophia, which must be the Byzantines’ greatest architectural legacy. While struggling not to reveal to my acquaintance my disturbingly inferior knowledge, I tried to remember who had built it. And as I sat in the attic, an unfinished book from my high school days came to mind: The Civilization of the Middle Ages by Norman Cantor. I bought it in twelfth grade because it seemed like a topic I should know more about, but I never made it past the chapter about the Byzantine Emperor Justinian (r. AD 527 - 565). Yes, I realized, it was Justinian who built the Hagia Sophia! And it was Justinian who codified so much of Roman law! I knew something after all, although it was so basic compared to the facts she was sharing that I kept it to myself. I remembered when I was 17 and bought that book, confident it would make me so smart. To think I never finished it! If only I had, just imagine the rarified commentaries I could add to this discussion in the lamplight of the attic! Instead I could only sit there, tormented by my lowly position on the socio-academic hierarchy.

Believing my acquaintance to be very sophisticated and scholarly, I came to imagine that perhaps the Byzantines who attracted so much of her attention must be equally refined. My ignorance about the Byzantines was thus a symptom of my own intellectual limitations. Despite all my past readings, I could see now that my Fantasy Self loomed still beyond my reach. Who was I, what was I, what value did I have if I could not put together a lecture about the Byzantines? For what had been all my dreams of possessing copious amounts of esoteric historical knowledge if, even at 23, I still could not sit in this apartment saying, “Oh, yes, I’ve read that volume too!”

These, I thought, are the just fruits of my idle dreams. I must take action. And so, leaving the attic full of elaborate plans for my education, I resolved to at last transform into my Fantasy Self. The one who sits around all day reading books about the Byzantines and never grows weary from the densest texts. But instead I decided to read some other book. And then at last, after an entire decade of irksome procrastination, I finally began to read in depth about the Byzantines.

But now, rather than being overawed by their supposed sophistication, I find myself deeply disturbed by the Byzantines. How I yearn to go back to that attic and explain how I hate them! Regardless of how often historians try to defend them, the Byzantines represent to me how centuries of relative enlightenment can eventually give way to an entire millennium of darkness and organized ignorance. I wonder sometimes if the Byzantines are a symbol of what might await our own society. They certainly demonstrate that we cannot take a Republic for granted; depending on our choices today, our descendants could be living in the most horrifying autocracy.

The Byzantines are the culmination of a lengthy transformative process which began with Greek philosophy and the Roman Republic… only to end with a totalitarian theocracy devoted to thought control. And although the Roman Republic was more a dysfunctional oligarchy than it was a popular democracy, the Byzantines suggest that the fate of a democratic system can be a stupefying religious tyranny. As the eventual successors of a republican government which collapsed into autocracy, the Byzantines make a mockery of the idea that the long arc of history bends toward justice.

Above: A gif of the Byzantine Empire over time (AD 476 - 1400), from Wikimedia commons

It was partly the notion of democratic collapse, rightfully in vogue during our time, which interested me in the Roman Empire to begin with. In the Romans, I found the true story I sought about how a republic can gradually, and then suddenly, give way to dictatorship. For centuries before Christ, the Roman Republic remained mostly stable under a convoluted electoral system weighted heavily toward the wealthiest citizens. But as the rich bought up small farms across the countryside and consolidated them into large villas built upon slave labor, ordinary citizens who had once owned their own land but now found themselves without livelihoods began flooding into the capital. In a system of government designed to serve the rich, it proved impossible to resolve the Republic’s intensifying socio-economic issues through elections. Populist reformers pushed through legislation to redistribute land to the poor, and they were killed for their efforts by thugs working for wealthy Senators.

As the idea that reform was possible through peaceful electoral processes became an obvious absurdity, struggling citizens turned to generals like Marius, Caesar, Pompey, Mark Antony, and Octavian. These military leaders could, either through bribery or the threat of arms, coerce Roman legislative bodies into passing bills that would distribute land to the soldiers in their increasingly private armies. The whole process was far more complicated, of course, and involved many other tensions, but after nearly a century of upheavals, the general Octavian seized total control of the state, reformed the constitution, and took the name Augustus (r. 27 BC - AD 14).

Augustus preserved many of the basic structures of the Republic, calling himself a “First Citizen” rather than a king, but he was in actuality the first emperor. After he had reigned for 41 years, hardly anyone alive could remember what it meant to live under the old Republic. The Republic’s institutions existed on paper, and the emperor was formulaically “appointed” by the Senate, but Rome had now converted fully into a military autocracy, even if its nature was disguised by the empty preservation of some democratic and oligarchic institutions. The military was loyal not to any abstract constitution, but rather to the emperor himself, so long as he served their interests.

The system was justified by the peace and prosperity it brought to the Mediterranean. For most people, life was significantly better, in a material sense, under the stable Empire than it had been under the chaotic and war-torn Republic. The Empire ushered in two centuries of security and trade.

Despite such fantastic peace, the real source of authority was violence. When local rebellions did occur, such as in Judea, the emperors put them down with uninhibited brutality. If the emperor was held accountable at all (and he sometimes was), it was only by members of the armed forces. Against these, the Senate’s only weapon was an appeal to ancient principles about which the soldiers, eager for the gold paid out to them whenever their new choice for emperor took power, could hardly care.

Over the next few centuries, the Roman emperors gradually did away with even the appearance of republican government. While Augustus had implausibly fancied himself as just another senator, taking his seat with that deliberative body and make-believing that they all still had power, his successors steadily abandoned these tiring charades. The system was sometimes unstable; the emperors were still accountable to their armies, who could and did revolt in order to install some preferred successor. After nearly two hundreds years of overall tranquility, more frequent rebellions culminated in a fifty-year period during which, in the third century, over two dozen emperors came and went. They claimed authority with the support of their soldiers - only to be killed by other (or sometimes the same) soldiers shortly afterward.

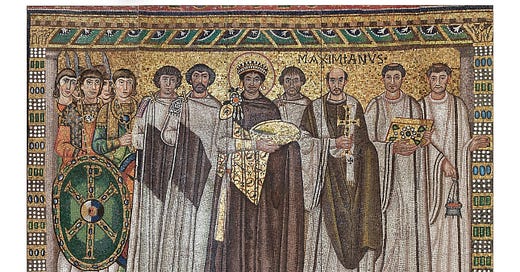

It was a great racket for the soldiers. They were paid a bonus called a “donative” every time a new emperor came to power. But throughout the more stable fourth century, under emperors like Diocletian, Constantine, and Theodosius, the emperors forsook the old “First Citizen” label and acted as god-like, mysterious, and distant figures, before whom subjects fell prostrate to the ground. In a servile age, the heightened ostentation of their authority perhaps granted them a greater degree of perceived legitimacy. They hardly spent any time in Rome, whose senators were increasingly ignored over the course of the century.

It was while reading the novel Julian by Gore Vidal, which takes place in the second half of the fourth century, that I imagined what it must have felt like once this escalating authoritarianism was combined with Christian zealotry. Before the emperors turned Christian, the spiritual beliefs of their subjects were hardly a concern to them. But once they fell under the influence of the bishops seeking to define orthodoxy, this changed. In an early chapter of Vidal’s novel, the pagan sophist Libanius describes the aftermath of a decree by the Christian Emperor Theodosius (r. AD 379 - 395).

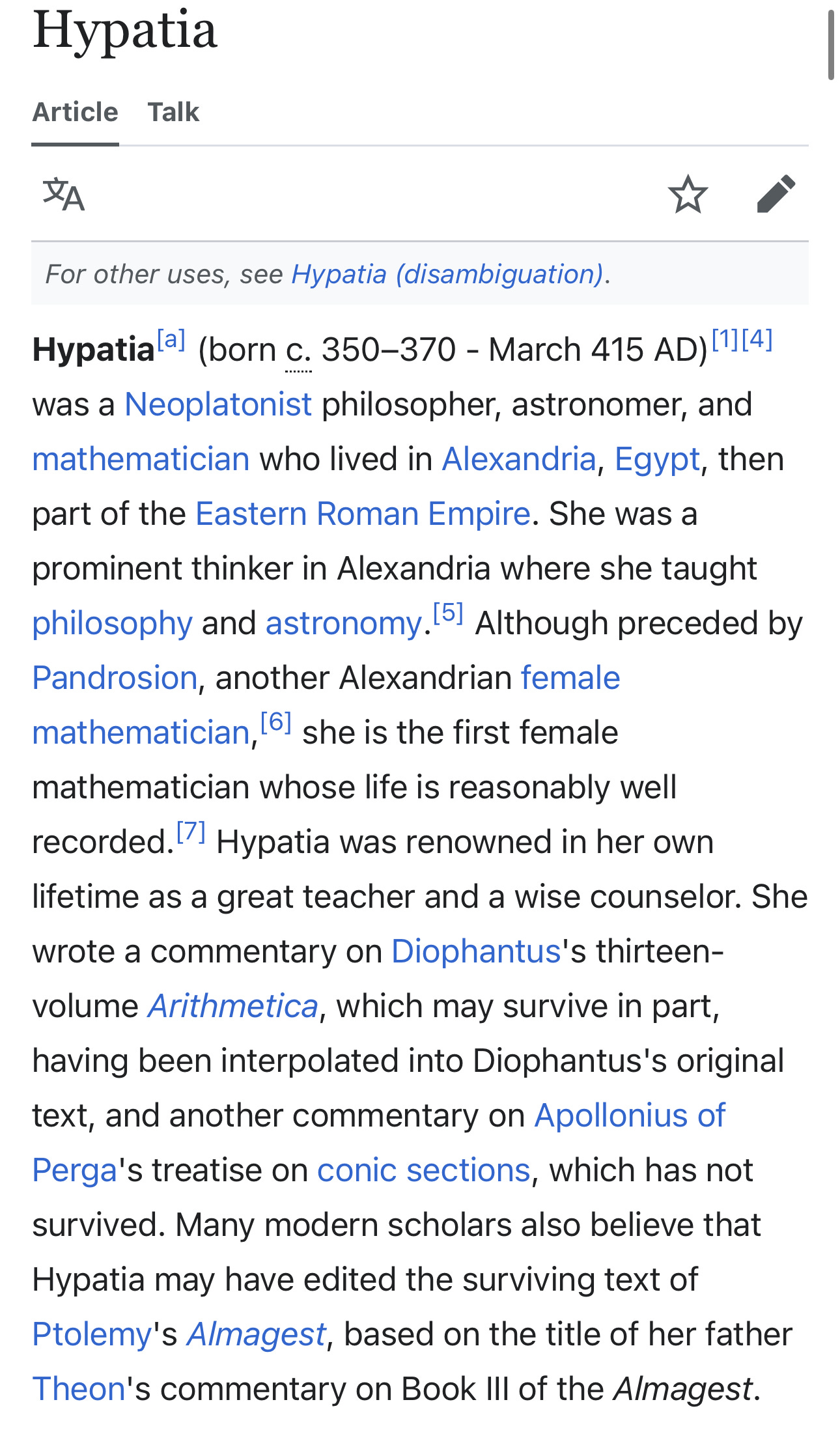

The Christians propagated a new concept into the mainstream of the Mediterranean World, namely that a person’s individual religious beliefs were of cosmic importance. Even the pagans who persecuted the Christians did not care what the Christians believed, so long as they went through the required motions of the rituals. For the pagans, belief was the subject of mostly free debate in the academies (so long as it did not challenge the emperor’s political authority or propagate outright blasphemy against the traditional gods). All sorts of philosophies about the nature of reality and the key to living a satisfying life proliferated. But whereas the old religious system, when it did make demands at all, had expected society to simply participate in the public festivals which honored the gods so as to secure the divine blessings for a general societal prosperity, the Christians demanded specific beliefs of people.

Yet for all their concern with imposing a list of doctrines upon society, the Christians themselves had a very difficult time specifically defining their creed. They gleefully killed one another over arguments which turned on the inclusion or exclusion of a single word. And even, in the case of the disputes surrounding the Nicene Creed and others to come, over single syllables and prefixes. Many historians will point out that, in the upheavals of their disagreements, the Christians persecuted one another over these trifles far more than the pagans had ever persecuted them. The bishops lobbied constantly for the Christian emperors to take action against their heretical enemies.

In the absence of stable political authority, the complete annihilation of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD was the occasion for greater influence in the West by the religious authorities of Rome. These increasingly rejected the doctrinal authority of the Eastern Roman Emperor, who controlled portions of Italy only intermittently from his faraway palace in Constantinople. But even if they had lost Rome itself, the emperors of the Eastern Roman Empire retained control over a vast domain including Syria, Egypt, Turkey, and Greece. As they intensified their despotism with the supplement of an increasingly obsessive religious totalitarianism, their rule was the ultimate capstone of the Roman State’s long march from republic to autocracy. Because in addition to political loyalty, the very thoughts of their subjects were now of paramount concern, and thought control thus became one of Christianity’s greatest contributions to Mediterranean history. This was a jolting transition for a society that had been relatively tolerant of religious diversity, and in which philosophies and cults of all varieties had flourished across society and in the academies.

It was the Emperor Justinian who, perceiving a hotbed of un-Christian thought, shut down the academy of Athens in 529 AD. Edward Gibbon, writing in 1788, points out that Christianity thus accomplished what the Gothic barbarian invasions which had once ravaged and looted Athens could not.

But the destruction of paganism and the suppression of Greek philosophy was not quite enough for the Christians. Neither the Byzantine rulers nor their subjects were content to simply enjoy a world in which the broad framework of Christianity was dominant. It was of vital importance to the emperors, the bishops, and many lay people that everyone in society comply with growing lists of highly specific beliefs. It was far from enough to simply accept Jesus as your Lord and Savior.

The vast majority of these disputes centered on what believers thought about the nature of Jesus Christ. To what extent was he God? To what extent was he a man? What was his exact relationship with the Father and Holy Spirit? What did all this mean in terms of Mary, his human mother? And was it okay to venerate his image and the images of the saints? The answers were viciously debated down to the level of each word, syllable, and prefix; the utterance of the wrong sound was sufficient for condemning a person’s soul to hellfire for all of eternity. These were the questions which turned neighbor against neighbor, sparked riots, spilled blood, and consumed the affairs of state. Countless emperors prioritized attendance at religious synods over defending the empire from military invasion. As Gibbon wrote over two centuries ago:

Animating many Byzantine emperors was a fanatical and terrifying yearning to ensure standardized compliance with the correct doctrines across the whole of the empire. Simultaneously, they strove to completely eradicate pre-Christian traditions. Naturally, successive emperors sometimes disagreed with one another over what the correct Christian beliefs were (even Justinian’s wife, the Empress Theodora, had a different understanding of Christ’s nature than he did). But they nevertheless treasured as their utmost priority the impossible imposition of religious uniformity across an extremely diverse empire containing numerous Christian traditions.

As I learned while reading A.D. Lee’s great book From Rome to Byzantium, this dynamic wasn’t completely up to the emperors. Their hands were also forced by Christian behavior. The culture had become intolerant, with doctrinal disputes regularly erupting in popular unrest. The emperors were under constant pressure from bishops seeking to impose certain doctrines, as well as from ordinary Christians who would riot in the streets if the local bishop subscribed to syllables with which they disagreed. Soldiers had to be deployed to restore order and impose new bishops on unwilling Christians, while angry Christians sometimes lynched bishops in the streets over slight Christological disagreements. To maintain order by orchestrating harmony out of the perpetual ecclesiastical discord, emperors sought to build consensus among bishops by holding synods… and then attempting (often without much success) to impose the findings of their synods across the whole of the empire.

The Eastern Roman Emperor Zeno (r. AD 476 - 491) is an interesting early case of this. In cities like Alexandria and Antioch, violence raged during part of his rule thanks to disagreements about the Council of Chalcedon. Chalcedon dealt with the extent to which Jesus was God versus the extent to which Jesus was a human; it had been held under the Emperor Marcian in 451 AD. Zeno at first sought to uphold the doctrines of Chalcedon, as later Byzantine emperors did. But then anti-Chalcedonian rioters in Antioch killed the Chalcedonian bishop there whom the emperor had appointed. A new one had to be imposed under the protection of imperial troops.

As tensions over Chalcedon escalated, Zeno decided to try a new strategy by crafting a compromise position between the Chalcedonians and anti-Chalcedonians. He hoped this would bring peace. As a part of his middle ground, which succeeded for a while in stabilizing tensions between the bishops, he issued the following ominous statement: “We anathematize anyone who has thought, or thinks, any other opinion, whether at Chalcedon or at any other synod.” This encapsulates the spirit of the Byzantines.

Zeno’s moderating position is now considered heretical by the Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox churches, and later emperors rejected it. Presumably, Zeno still burns in Hell even as I write this. Unless he was right, of course; then most Christians alive today are doomed. Tensions over Chalcedon would later help rip the Byzantine Empire apart when anti-Chalcedonian Christians welcomed the Muslim invaders. These proved more tolerant of their views than the Chalcedonian emperors had been. To this day, the Ethiopian, Syrian, and Egyptian churches reject Chalcedon.

An emerging religious despotism is what fundamentally characterizes the transformation of the Eastern Roman Empire into the Byzantine Empire. As the Byzantines called themselves Romans until the bitter end (and even their Ottoman conquerors fancied themselves the new rulers of the Roman Empire), there is no year which can be objectively cited as definitive. But it is clear that while the classical Romans had been tolerant of many religious traditions, the medieval Byzantines seem to have been unwilling to suffer diversity even when they found it under the umbrella of the same religion. Meanwhile, partly by being crowned by the hands of the Patriarch of Constantinople in a religiously fervent society, the Byzantine emperors attained a level of unquestioned autocracy never reached by the Romans.

Historian JM Roberts discusses this development in his book The Penguin History of the World. As he explains it, the Eastern Roman emperors achieved a supreme political and religious authority. While the space which had been the Western Roman Empire was often characterized by a tug-and-pull between ecclesiastical and political authorities, the regions controlled by the Roman successors of the east contained no independent sacerdotal entities who could really challenge the emperor.

There was no true equivalent in Eastern Orthodoxy, Roberts observes, to the pope. The bishops of Rome were able to take advantage of the collapse of western imperial authority, and tensions between the papacy and various kingships prevented the concentration of absolute power. Both popes and kings often needed one another in Western Europe. But the priests and bishops of the east, where Roman imperial authority maintained its steady hand for another thousand years, enjoyed no such opportunity to fill any sudden political vacuums. Instead, there intensified the tradition stretching back to the Roman Emperor Constantine (r. AD 306 - 337) and the Council of Nicaea (AD 325) where the emperor, rather than the bishops, was the ultimate arbiter not just of political but also of religious disputes. The Byzantine emperor was thereby to become the ultimate autocrat, with constitutional domination over both the church and the state simultaneously. As Roberts puts it:

The Byzantine emperor was the ultimate culmination of the process which began with Augustus. He was the climax of the long evolution by which a failed republican government gave way to a suffocating autocracy. And as Roberts points out in The Penguin History of the World, the emperors’ domination over their empire was only enhanced when the Muslim armies seized from them those provinces in Syria, Egypt, and portions of Turkey which were the cradles of the anti-Chalcedonian churches. The Christians of these places, long oppressed by their fellow followers of Christ in Constantinople, welcomed the Islamic yolk as a relief from Byzantine intolerance. And although it meant a loss of glory, the emperors might have been happy about it too. The empire had been overextended anyway, and once it was smaller, the Orthodox Church became more stable, “having to make fewer concessions to religious pluralism as previously troublesome provinces were swallowed up by the Muslims.” Imperial contempt for diversity certainly cost the Byzantines territory, but the more doctrinally homogenous space which remained must have eased the realization of autocracy.

But what remained could not endure forever. The empire was surrounded by political and religious enemies who coveted its lands. Various Muslim, Catholic, pagan, and even some Orthodox armies emerging from Europe, the Middle East, and Central Asia slowly chipped away at a shrinking imperium. It was the Ottomans who ultimately finished off Constantinople in 1453. On the day of the final assault, after over 50 days under ruthless siege, the last Byzantine emperor led his people in prayer within the great church of St. Sophia before heading into combat with his men. By the end of the day, he had disappeared in fighting, his body never found. What had once been the largest Christian church was converted into a mosque that very evening.

The Byzantine emperors had been engaged in an ill-fated and hopeless quest to impose doctrinal uniformity upon an extremely diverse society, and it was these very policies which weakened their hold over their many far-flung territories. Along the way, their lands were eaten up by enemies as varied as Catholic Crusaders, Scandinavian raiders, Venetian naval expeditions, Arab caliphs, and finally the formidable Turks who emerged from Central Asia. Once nearly all their territories were lost, they could only hide behind the impenetrable walls of Constantinople until the age of gunpowder. Then the Ottomans arrived with artillery and finished them off.

The Byzantines were no more, and I suppose I would thank God for it. But during the crucial centuries of imperial rule, Byzantine bishops had succeeded in converting most of the Slavs before Rome could. The Byzantine missionary St. Cyril (AD 826 - 869) gave his name to the Cyrillic alphabet used for so many Slavic tongues, and which helped spread Christian scriptures among the Slavs in writing. Yet he was also a diplomat serving what Roberts calls Byzantium’s “ideological diplomacy,” whereby “missionaries cannot be easily distinguished from Byzantine diplomatic missions.” Efforts at conversion were intense and definitive of Byzantine foreign policy. With the conversion of most Slavs to Byzantine Christianity, these efforts paid off.

The Byzantine religious legacy remains with us today as Eastern Orthodoxy. And once the Byzantines were destroyed, it was Slavic Russia, with highly autocratic structures resembling those of the Byzantines, which claimed itself as Defender of the Faith. The tsars of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries styled their Moscow as the Third Rome; they were successors to Augustus and Justinian, self-proclaimed champions of Orthodox Christian faith, inheritors of the Roman Empire. Of course, the Muslim conqueror of Constantinople had other ideas, immediately declaring himself “Caesar of the Romans” and placing himself in a long line of autocrats going back to Augustus.

Long ago in that apartment, I was convinced by the sophistication of these mysterious people. But now, the word “Byzantine” signifies to me the final transformation of an ancient republic into a thought-controlling theocracy with the ability to endure in a state of grotesque darkness for a thousand years. Fortunately, the Byzantines were doomed from the beginning, although they carried on like zombies in the shadows of their elaborate churches, living for centuries under a grim ecclesiastical tyranny.

I am simply unable to agree with those historians who reject the term Dark Ages for Europe during this time. Decrying the whole concept is deeply in vogue these days, as is the defense of the Byzantines. Some historians even use Byzantium as their example to contradict the notion of a Dark Age! But those who champion the Byzantines by pointing to their material achievements, or to their political stability relative to the destruction of the Western Empire, have missed the true meaning of darkness.

While the term is usually used to describe the violence and illiteracy of Western Europe, I feel that it must also be applied to the staggering intellectual emptiness which prevailed beneath all the glittering wealth and beautiful architecture of Constantinople. Centralized authority and glamorous buildings are simply not enough to reject the notion of a Dark Age. The pleasures of meagre luxury cannot compensate for the subjection of so many souls to a sickening intolerance and closed-mindedness generation after generation for nearly a thousand years. Nor can the long survival of a ruthless theocratic regime inspire my admiration. However “advanced” they were relative to the Western Europeans, the lives of the most prominent Byzantines were just as pathetically consumed by the most absurd concerns. Neither the mindless preservation of ancient Greek texts nor the use of Aristotle in their theological commentaries can ever redeem such a pitifully degenerate and servile culture.

next:

the rise of religious totalitarianism in the former western roman empire (the construction of the catholic church, papal power, and modern catholic rituals)

for what happened in the Eastern Roman Empire: