the rise of religious totalitarianism in the former western roman empire (the construction of the catholic church, papal power, and modern catholic rituals)

how the Catholic Church gradually established religious totalitarianism in the former Western Roman Empire (I love you Phoebe: you make my heart a history class — literally ❤️)

world history: all my links in one place ! 💖⭐️🌟💫💗💞🧙🌍🌏🌎

Proceed chronologically or start with any topic!

Next:

Malta and the Celebration of Christian Nationalism (October 19, 2022, the severed branch)

A street in Valletta at sunset (photos my own)

dublin and the severed branch: where Phoebe transformed me from materialist to spiritual

I was visiting my brother-in-law, who was working while I was there, and I began each day setting forth alone a bit after eight in the morning. I walked the half hour to Merrion Square in the pleasant chilly autumn air, feeling so satisfied by the brisk sensation against my skin and inside my throat. I could not comprehend the people saying I needed to …

special credit to Peter Heather whose research has been invaluable to me

The day Pope John Paul II died, my house erupted with joyful songs celebrating his demise. “Ding dong the pope is dead, the wicked pope is dead.” Only a few months before, I too would have eagerly commemorated the passing of that wicked and idolatrous man. I had spent so many months convinced that all the papists at school were doomed to burn in Hell and that their beloved leader in Rome was the Antichrist. But now, such abject callousness toward the supreme western priest struck me as deeply disrespectful. And so on the day John Paul II died, I took refuge in the shadows of my bedroom, avoiding my Calvinist persecutors’ triumphant celebrations. I yearned to fall prostrate on the ground before the holy office of the papacy.

I had first planned on becoming a Catholic because a girl I liked in middle school was supposedly a Catholic. In truth, I was not actually sure if she was a Catholic. But she was planning on going to the local Catholic high school, and I wondered if I should go there too. I had always hated Rudy, but maybe I could embrace Roman Catholicism as a way of defying my Protestant parents. It would be a more pious approach than the one I had taken in early elementary school, when I shouted at a Christian institution’s whole-school assembly that “I don’t pray to God; I pray to Satan.” It would have been so edgy and rebellious to follow that up by shifting my allegiances from the Holy Spirit to the Pontifex Maximus. The latter of these two important posts, after all, is an office preceding Christ himself, having been occupied by Julius Caesar several decades before Jesus was even conceived by Mary and Joseph. But those dreams ended when I realized I might need to find a new group of friends to play Halo with in the basement, and so I followed my fellow video game addicts to the public school.

The days after Pope John Paul II died were different. I had finally accepted the theory of evolution, but I was not prepared to concede that I was as much an animal as any other ape. Having previously believed without doubt that I possessed a celestial destiny, my exclusively earthly origins were deeply troubling. I had to abandon the gratifying nightmare that I myself might be the Antichrist; the fame alone would have been worth my eternal fall into the darkness of the Abyss, and I would at least be a crucial component of God’s plan for humanity. It would have given me a certainty about my purpose in life. It couldn’t be that my life had no more meaning than a monkey’s. I sought something in my essence that was more than mere flesh.

Yet now, in the midst of the disorienting realization that my distant cousins were chimpanzees, I needed to rethink what I believed about the soul. I kept believing in my three celestial overlords not because I thought their existence made sense but because I was terrified of the moral chaos and meaninglessness their absence might incite. I knew the truth to it all must lurk somewhere within the Christian tradition, not because I had learned anything about any other religion but because I knew all humans were innately evil and thus needed the sacrifice of Jesus for their salvation. But even if I still needed Christianity, that couldn’t help me choose the precise set of doctrines that would secure my place in Heaven. I had lost countless nights in tenth grade analyzing the websites of all the different groups: the Southern Baptists, the Lutherans, the Presbyterians, the Methodists, the “Nondenonominationalists,” and of course their many various subdivisions. It turns out, for example, that there are something like 20 different types of Baptists. This was the chaos which the Protestant Reformation had unleashed in the 16th century by declaring that every man must read the Bible for himself and discern the Scripture’s truths on his own. Then he could shepherd his women and girls toward a chaste and devout understanding.

It seemed so freeing at first, the right to read and think about the Bible on my own. But the stakes were so high. I knew plenty of Protestants who thought that other types of Protestants would burn in Hell forever, having been one myself. I was certain for a long time, of course, that I possessed the true interpretation of the Scriptures. My parents, succumbing to the Preterist heresy, had come to erroneous eschatological understandings about the meaning of several vague biblical prophecies in Revelation, and for that I feared that God would hand them over to the demons with the other heretics. Close as they might be in Hell to my great grandfather, who would also be burning there as his rightful punishment for being a Mason, she and father would find no comfort in those flames. Still I warned them: “You know your grandpa is burning in Hell, right Dad?” And I told my mother to her face that perhaps she would not be welcome through Heaven’s gates. But I found solace in the knowledge that even as my mother and father were screaming in the Lake of Fire, my heart would nevertheless be filled with joy, for I would be standing at the right hand of the Lord, preparing my vocal cords for eternal worship. Unless I went to Hell too for masturbating.

Remembering my sacred vow to never have sex married or unmarried, I plotted out my career as a priest. It was a goal which animated me for a couple of days before fading away just like my older dreams of becoming a geneticist or a policeman. I did have one crucial concern. Could I really persevere in celibacy like the priests do? Although it was true that my masturbation addiction had required the failed intervention of an online Protestant mentor who kicked me out of the program after just over a week, I was sure I could control myself once I was seated at last on the receiving side of the confession booth. In fact, my failure to resolutely resist the most easily anticipated adolescent temptations might have resulted from my soul’s residence outside the one true universal church. If only in my boyhood I could have simply confessed my masturbation habits to a caring priest, then he could have absolved me and given me my penance. A priest would not have given up on me. He would have guided me to higher levels of sexual purity. Or at least he could have forgiven me in Christ’s name, an action for which no Protestant pastor could ever claim the authority. I could have gone to sleep at night believing I was going to Heaven instead of fearing that God might send me to Hell for lusting after boys at school.

Regardless of my prospects for priesthood, I had grown weary of discriminating between the religious options on offer at the multitudes of Protestant churches. And I had grown even more tired of analyzing which of my friends would go to Hell and which would go to Heaven based on how they answered certain questions. To set me straight and handle such matters, I required the sharp and caring whip of the supreme patriarch; I craved a man who could simply tell me the correct interpretation of the Scriptures. I needed a level of assurance about my salvation which Protestantism was incapable of providing, and the firm structures of Catholicism promised this.

True, the Protestants had taught me that I could have my own direct relationship with Jesus without requiring the intercession of a divinely consecrated male celibate. “It’s not a religion,” they say, “it’s a relationship.” And I did become intimate on occasion with the Lord, in particular when I was reading the Bible to help me stop jerking off. But nevertheless, I then found myself indulging in the fleshly passions even as the Holy Scriptures were opened up before me. I knew I would go to Hell for it, and I knew that, as Jesus said, there was no real difference between lusting after a man in your heart and actually fornicating with him, but somehow it was still worth it to me. So my supposed relationship with Jesus, no matter how closely I sensed His presence, was in the end insufficient for making me into a better person. How could I ever have been such a fool as to think I had some kind of friendship with a man who had the power to cast me into eternal flames and watched me at every moment? Leaving my relationship with Christ behind, I preferred now to see Him as a distant king, and I craved the oppressive structures of the organized religion which constituted His earthly bureaucracy. The Vatican offered me assurance which Protestantism could not: salvation by virtue of my confirmed membership in an international organization and the regular accomplishment of a few bizarre rituals. I could even keep masturbating so long as I made regular reports about these dark deeds to a priest. And was it not true, after all, that Jesus said He built His church upon the rock of St. Peter?

It was only later that I realized the pope’s position as head of the Church was a historical development which took over a thousand years from the point of St. Peter’s death. The bishop of Rome, it turns out, was important in early Christianity, but was not anything like a final authority. The office in Rome was just one of five Apostolic Sees, each competing with the other for influence over still crystallizing Christian doctrines; the others were in Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria, and (from the fourth century on) Constantinople.

As Peter Heather documents in his book The Restoration of Rome, the true head of the Church was not the pope at all, or even any of the bishops working collectively, but rather the Roman emperor. Only the emperor had the authority to call an ecumenical council assembling all the Christian bishops into one place. And only the emperor, acting as a sort of one-man Supreme Court of Christianity, had the authority to settle the doctrinal disputes which inspired the ecumenical councils which he summoned. The Emperor Constantine established this pattern at the Council of Nicaea in AD 325, so that the core creed of virtually all Christians today was originally a Roman emperor’s decree. For a long while after Nicaea, the Roman emperors and then the barbarian successor kings of the old Western Empire were the virtually unquestioned heads of the Christian Church. It was not until the First Lateran Council of 1123 that the bishop of Rome summoned an ecumenical council.

Heather documents how the bishop of Rome’s power unevenly increased over the centuries after the Western Roman Empire’s collapse in 476 AD, thanks to a number of factors and forgeries. Despite their distance from the regions of the old Western Empire, the Eastern emperors in Constantinople still considered themselves the ultimate authorities of the whole Christian world. And Eastern forces controlled Rome itself for nearly 200 years after Constantinople’s sixth century conquests on the Italian peninsula, so that for a time the pope had very limited autonomy under the thumb of Byzantine representatives. But as East and West drifted further apart over time, Byzantine claims first seemed implausible and then lost their effect.

The Byzantines (East Romans) were weakening in the eighth century, losing territory to Muslim invaders and facing mutinies by the unpaid soldiers in Italy, whom they began compensating with land. The papacy was able to take control of many Byzantine properties left behind while balancing the interests of the new noble class that emerged from the officers. And after the Muslim armies conquered the apostolic sees of Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem, what had formerly been an integrated Christian world centered upon the Mediterranean became even more fragmented, while simultaneously leaving the bishop of Rome as the only apostolic authority with any presence in the regions of the old Western Empire, finally free from the Eastern Empire’s dictates. Meanwhile, Heather argues, the claim of the Byzantine emperors that God had anointed them as the supreme Christian authorities lost significant credibility once that same God allowed the Byzantines to lose so much land to the Muslims. The Eastern emperors must, those in the old western provinces thought, have committed some grave crime against the Lord. But even all this was insufficient for establishing the papal authority to come. Although the pope was important, Heather describes him as having been something like the Christian version of the American Vice President, certainly valuable symbolically and certainly listened to when he spoke, but without possessing any genuine authority in practice. Instead, the reduction of East Roman power and an ensuring legitimacy crisis paved the way for Charlemagne, the great Frankish conqueror, to make his own claim of emperorship. God had favored him in war, and this was a signal that he was divinely chosen.

On Christmas Day 800 AD, when Constantinople’s presence in Italy had been reduced to a few small outlets, Charlemagne had himself proclaimed Roman emperor by the pope. In the title of emperor, Heather explains, he understood himself as possessing both temporal and spiritual authority. As his empire united greater portions of Europe than had been achieved since the Western Empire’s collapse over three centuries earlier, he had become the head of the Church not only in name but also in practice. He summoned his own synods, such as one at Frankfurt in 794 AD, which came to different verdicts than those of the Eastern Emperors, and he cultivated the preservation of numerous ancient Christian texts while reviving the Latin traditions that had been lost. It was he who appointed the bishops in his realm, it was to him that these bishops answered, and it was to his generosity that the monasteries, flush with complete copies of once corrupted Christian writings, owed their gratitude.

Long after Charlemagne died, it would remain the kings and emperors who appointed the key churchmen in their kingdoms. Leading the Church was, they considered, among the core responsibilities of Christian kingship, and the pope had little to do with it. Simultaneously, however, Charlemagne had strengthened the papacy by granting it political control over large swaths of formerly Byzantine Italy and defeating its enemies, the Lombard kings of northern Italy. The pope had not crowned Charlemagne in exchange for nothing. With its new lands, the papacy gained access to tax revenues and customs duties, while Charlemagne further directed a steady stream of precious metals into the coffers of Rome’s religious institutions. All this nurtured the foundations for an even more powerful papacy in the centuries to come.

Nevertheless, for a long time, the popes retained only limited influence and control over what were effectively several different “national” churches scattered across Western Europe with their own kings and emperors as heads. Heather summarizes the situation as it persisted from the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, when a single Roman emperor was the indisputable head of the Church, and on into the ninth century six hundred years later, when successions of kings and emperors exerted control over what were often separate church infrastructures:

But as Heather explains, there were many churchmen who came over time to resent the religious powers of their kings, and there were many popes who sought a basis for their own authority. Hints of justifications for such power first appear in a papal letter from 778 AD, when the pope references “the most pious Constantine of holy memory, great emperor, who designed to bestow power in these western regions upon [the papacy].” The origins of this claim’s documentary basis are murky. But Heather suggest that, perhaps in an effort to balance the power of the kings against some other external force, Frankish religious scholars put together the final forgery, called the Donation of Constantine, which would justify appeals to Rome in their arguments with their political leaders.

A fabricated imperial decree, it claims that the Emperor Constantine, before he departed Italy for his new capital in modern Turkey, bestowed political and spiritual power over the whole of the Western Empire upon the bishop of Rome. The religious scholars who created this deceit, hundreds of years after Constantine died, included it inside what they had assembled as the then-largest single collection of the early church documents. Containing an elaborate mixture of fraud and reality, this huge compendium quickly became an indispensable resource for Christian scholars across the old Western Empire. Some questioned certain documents, Heather explains, but ultimately this authoritative assemblage was diligently duplicated across monasteries, abbeys, and churches, becoming nearly ubiquitous by the late tenth century, and numerous men had an interest in accepting it. Even Charlemagne himself took interest early on, since it seemed to create a legal basis for his coronation as emperor by the pope, who had won the power from a former emperor. But over time, the Donation of Constantine also helped give a series of future popes the ideological confidence they needed to assert their own authority over church affairs across the old Western Empire. It also gave churchmen across the same region a new justification for sending direct appeals to the pope when they found their kings disagreeable. Thus began a long process by which the pope would slowly gain control over more and more church infrastructure, even that which lay beyond the Papal States of Italy.

How else, though, to awe the peasants, the churchmen, and even emperors themselves into submitting to the pope’s spiritual authority? The Christian churches had long ago mastered the art of appropriating pagan idolatry for its own purposes. They knew the masses required holy sites, saints, relics, and icons to supplement their worship. In the spirit of endowing their religion with a new level of sacred mystery, the bishops of Rome invented the evermore inexplicable and bizarre rituals which many Catholics today accept without interrogation as among the most ancient and sacred rites of their religion. This great reform movement, which revolutionized the Catholic Church and helped shape it into what it is today, largely took place over a thousand years after the birth of Christ. As JM Roberts puts it in The Penguin History of the World:

According to both Heather and Roberts, the practices which the Church of that late era established include transubstantiation, regular confession, the celibacy of priests, marriage as a sacrament, and even regular attendance at Mass. In suddenly taking on a more direct role in the administration of marriage, which was not actually declared an official sacrament by the Church until 1563, the Church became more obsessed with the sexual purity of individuals. And yet on the day His Holiness the Pope John Paul II died and joyful celebrations were erupting in my house, I imagined that maybe the Pope was the protector of traditions stretching back all the way to the moment when Jesus handed over the keys to Heaven to the Apostle Peter. Perhaps I needed to attend Catholic church and drink the blood of Christ through the miracle of transubstantiation; maybe I really was obligated to go and confess my sins to a priest. But I thought this only because I had no idea how recent were both the establishment of papal authority and the invention of the rites over which priests preside. To think it was all designed over a millennium after the death of Christ, and that the human office which created it all would eventually go so far as to claim for itself infallibility!

Hildebrand (known to Catholics as Pope Gregory VII) was among the decisive bishops of Rome in that era who helped invent practices having little to do with Jesus Christ or the Gospel. Elected pope in 1073, he “fought all his life for the independence and dominance of the papacy within western Christendom” (Roberts). It was he who established the practice of electing future popes in the College of Cardinals, and he did it as a political move to protect the office of the papacy from noble influence. Hoping to further separate the clergy from society, he campaigned to impose celibacy upon priests and ban priests from marriage, although this would only become enforced Catholic policy from the twelfth century onwards. He worked to shut secular authorities like kings, bishops, and other nobles out of the appointment of bishops and abbots, and he even dared to excommunicate an emperor from the Church. In Gregory’s mind, the pope’s power over both the spiritual and the temporal was absolute; kings must be vassals to the papacy. Obviously this last bit could not be easily enforced, although he did manage to force the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV to fall to his knees pleading for forgiveness while Gregory left him waiting for three days and three nights in a blizzard. It was a seminal moment for medieval papal supremacy, and Gregory’s efforts launched the papacy on its path to the kind of spiritual authority it wields today. In the following two centuries, church practices would morph by human design into the mysteries before which ordinary Catholics still stand in devoted awe; by creating new rituals, making them essential, and controlling access to them, the popes could further cement their power over the minds of European peasants and nobles alike. As Roberts sums up that time period:

Sometimes I listen to choral music from the thirteenth century. I listen to the harsh chords of a giant organ, and I hear the voices lifting up their praises to the Lord. I imagine all these singers crowded inside a gloomy and disease-ridden medieval cathedral. They are the people who marched all the way to the Middle East in the Crusades. They murdered Jews, raped women, and ransacked the Byzantine capital of their Christian brethren. They slaughtered countless innocents when they finally captured Jerusalem. Frightened but obsessively curious to gaze into the face of one of these men, I open up The Restoration of Rome and flip to the pictures in the middle. There, in the innards of a book which they would have burned me alive for reading, I stare with stupefied terror into the sinister eyes of His Holiness the Pope Innocent III.

Elected pope in 1198, his papacy was a kind of capstone to the horrors which his predecessor Gregory VII had promoted. Both of them were firm believers in the need for Christian military might to secure the Holy Land from the Muslims, and each was a staunch proponent of new levels of papal supremacy. In the spirit of the Donation of Constantine, Innocent III claimed authority over all the kings of Europe. At the same time, he presided over a massive gathering of bishops from all across the Continent and its islands at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. It was then that the Catholic Church formally adopted the cannibalistic idea that the bread and the wine at communion become the actual body and blood of Christ. And out of that crucial medieval ecumenical council, no longer subjected to the authority of the once almighty Christian emperors, a more determined standardization of sexual behaviors and beliefs also emerged. It was enforced by the duty of bishops to preside over lay “morality” and to destroy the heretics whom they were admonished to find.

Implementation was slow-going and reached the priests much faster than it did the common peasants of the countryside, but not even the most remote villages were exempt from this new project of sexual totalitarianism. Heather describes papally appointed inspectors traveling around England in the late thirteenth century to uncover and correct widespread adultery as they strove to enforce the priorities established by the Fourth Lateran Council. Their records are preserved and reveal an impoverished English village in Kent enjoying a multitude of illicit carnal passions; these the Pope’s sex-obsessed investigators sought to meticulously document and hopefully restrict. I imagine the pious vision for the world which men like Gregory VII and Innocent III had, and I am so grateful that they were unable to fully realize their project to subjugate the whole of humanity under their rule. Then I remember that these monsters created many of today’s most cherished Catholic rituals, and the entire Catholic edifice crumbles before me as nothing more than an elaborate fraud.

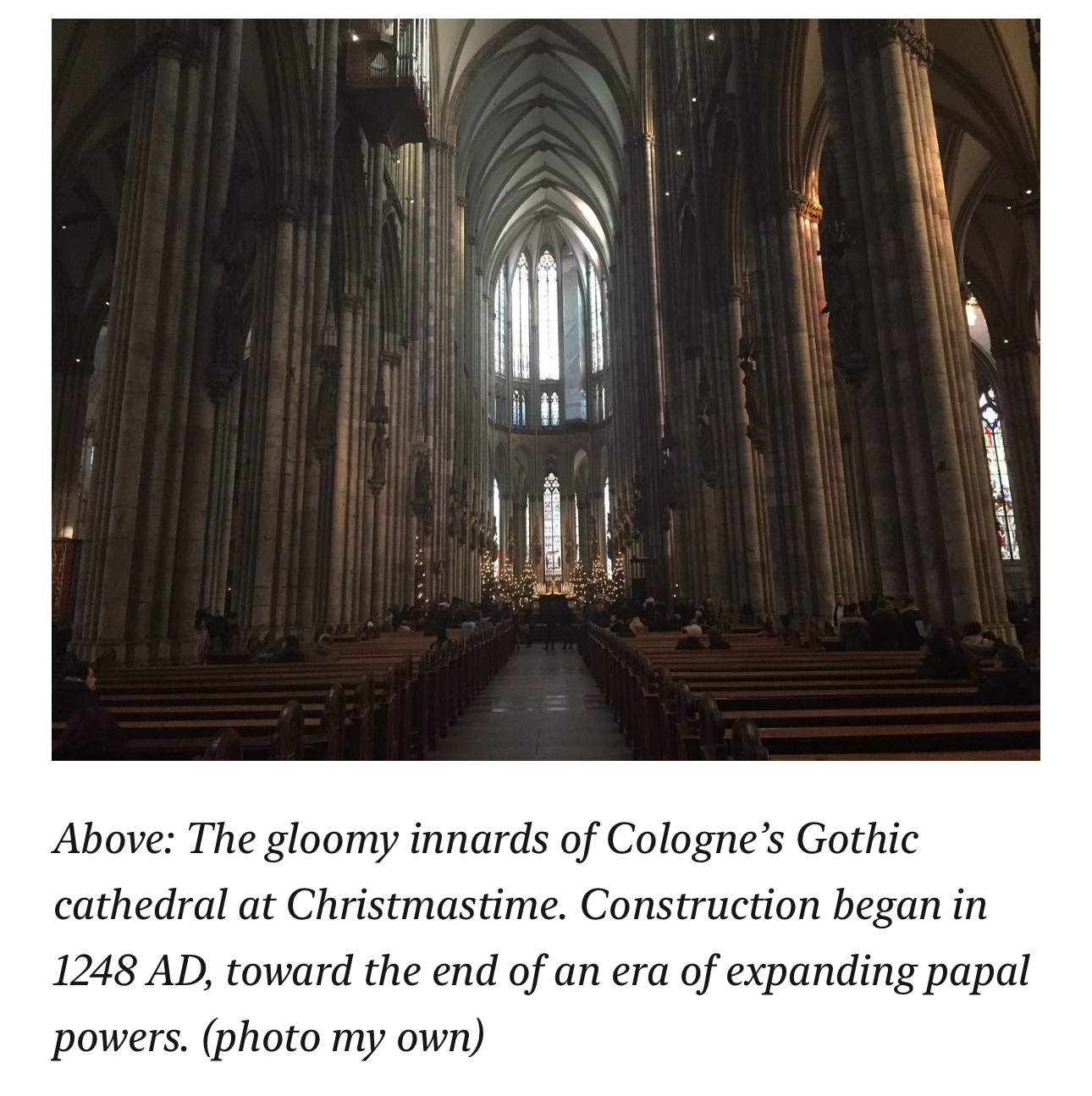

The construction of vast Gothic cathedrals went hand-in-hand with new doctrines and practices to strengthen the church’s iron grip over the ignorant minds of the medieval Europeans. To achieve the latter aim, the Church did not necessarily need direct political power, although it had this across large portions of Italy. Instead, so long as access to these human-invented rituals was essential to salvation, the Church’s monopolistic administration of the sacraments gave it new forms of power over the lives of its parishioners and even over the political leaders to whom it might deny communion. No matter that the priests rather than Jesus had invented these supposedly essential rites; hardly anyone could read the Bible for themselves to find out, and so the Church strove to ensure it would remain. Illiterate peasants, who might question the right of the Pope to claim the awesome authority which sapped them of their food in the name of building churches, were silenced the moment they set foot into the staggering innards of the great cathedrals. These incredible buildings were like miracles testifying to the clerics’ divine right to a spiritual dictatorship.

Little of this had real basis in the original teachings of Jesus or in any of the church traditions which emerged in the few hundred years after Christ’s death. By inventing such rituals anyway and insisting on their necessity for salvation, the popes effectively claimed authority which only the Lord Jesus Christ could truly hope to have. In doing so, they further complicated the simple message of faith and faith alone in Jesus Christ which constitutes the Gospel, adding their own additional requirements for eternal life simply so they might fortify their earthly power. It is in this sense that the Pope is in fact the Antichrist, having brainwashed multitudes of Christians into accepting his self-proclaimed spiritual sovereignty and having deceived countless generations away from the purity of the Gospel: “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.” But that simple message would remain obscured by bizarre rituals until it was revived during the Protestant Reformation, which also challenged the church by expanding access to the Bible in vernacular languages and encouraging the spread of literacy so that people would read it. Fortunately, that 16th century Protestant revolt, which both rejected the Church’s claim to be able to forgive sins in exchange for money (a system for selling indulgences) and proclaimed Faith and Faith Alone as its core motto for salvation, significantly weakened the Catholic Church’s stranglehold over Christianity in general. Nevertheless, Heather considers the papacy’s triumph so complete that he dubs it a “second Roman empire,” one which still exerts remarkable ecclesiastical control across international boundaries.

I never did submit to the papists’ yoke. Although I only knew bits and pieces of this history at the time, I was aware of the grounds for the Protestant Reformation, and I had heard plenty about the overwhelming combination of corruption, abuse, wickedness, and reactionary fanaticism which continue to plague the Vatican. When the College of Cardinals met in 2005, as had been commanded by the medieval Gregory VII, they claimed a divine authority to appoint the pope which I could not accept. Then the spirit of God apparently led them to select the right-wing Joseph Ratzinger as the supreme western celibate. I had been a Protestant for too long to see anything in the Catholic Church but a betrayal of the Gospel’s simplicity, and I thought Benedict was far too hideous to be worthy of my devotions.

When I told Catholics at school about my scheme to become one of them, they were troubled and disturbed that anyone would actually choose to be a Catholic. It startled me how different this behavior was from the Protestants, who are so intent on expanding their ranks that their wealthy megachurches send hoards of buffoonish missionaries to convert Catholics in Latin America. But the Catholics warned me to stay away, literally laughing out loud at the mere idea that I would willingly convert to their oppressive religion. The priesthood seemed ever further out of my reach.

Soon I rethought my dreams of eternal celibacy; I was dating a Lutheran girl with whom I went to Lutheran church. The Catholic seminary could not be for me, and I didn’t want to confess the struggles of my flesh. I was slowly embracing the hedonistic joys of animalism, at last finding much pleasure in sin. “I am agnostic,” I eventually started telling people, “but I am certain that Protestant Christianity is most likely to be true.” My old “relationship, not religion” with Jesus haunted me in a way I couldn’t shake, convincing me that I somehow had some answers, scaring me away from truly considering ideas which might betray Him, but not strongly enough to keep me from routinely breaking His sexual commandments. I would say sorry later. In the meantime, I couldn’t recognize a priest’s right to intercede between me and my Lord. I needed Him right next to me; I needed Him to be my friend, and I clung to Faith and Faith Alone. In that way, I abandoned my old anxieties about doctrines, and I dimly believed in Jesus. But an unelaborated and un-interrogated faith was an approach to salvation which even many Protestants, consumed by anxiety about changing notions of sexuality, gender, and human origins, had by then forsaken in favor of their own relentless qualifications to the purity of John 3:16.

Unable to sustain my belief in the spiritual as I built up a new confidence in the awful emptiness of a strictly material and uncreated universe, I gave myself up to a sensual godlessness which was never quite so dissolute as I aspired for it to be. My old Christian conscience reprimanded me, but I suppressed it and lived for the moment. In the quest to fulfill the yearnings of the flesh, I abandoned all hope for salvation and slowly learned to embrace my growing fears of the eternal nothingness to come.

Sources:

Peter Heather, The Restoration of Rome

JM Roberts and Odd Arne Westad, The Penguin History of the World

Malta and the Celebration of Christian Nationalism (October 19, 2022, the severed branch)

A street in Valletta at sunset (photos my own)